Over five years ago, I ran a podcast for Operation Code, an organization helping veterans and their spouses get into technology. You can still listen to it. One of the interviews, Dick Sonderegger, has stuck with me, since he had such amazing stories about his time during the Vietnam era (spoiler: he never left the US). The title refers to the fact that Marines made him become a programmer, even though it wasn’t his choice.

At the time I did this, text transcription was pretty lousy, but nowadays you can install MacWhisper on your Mac, and it is incredible! I had to do a small amount of editing on this transcription, but very little. It even knows to ignore the verbal tics (“um,” “you know,” etc.) You can listen here.

The Interview

[music]

[Intro] Hi, I'm David Molina, founder and board chair of Operation Code. Our mission is to help veterans, transitioning service members, and military families learn software development, enter the tech industry and code the future. Please visit us at operationcode.org. And don't forget to like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. I hope you enjoy the show.

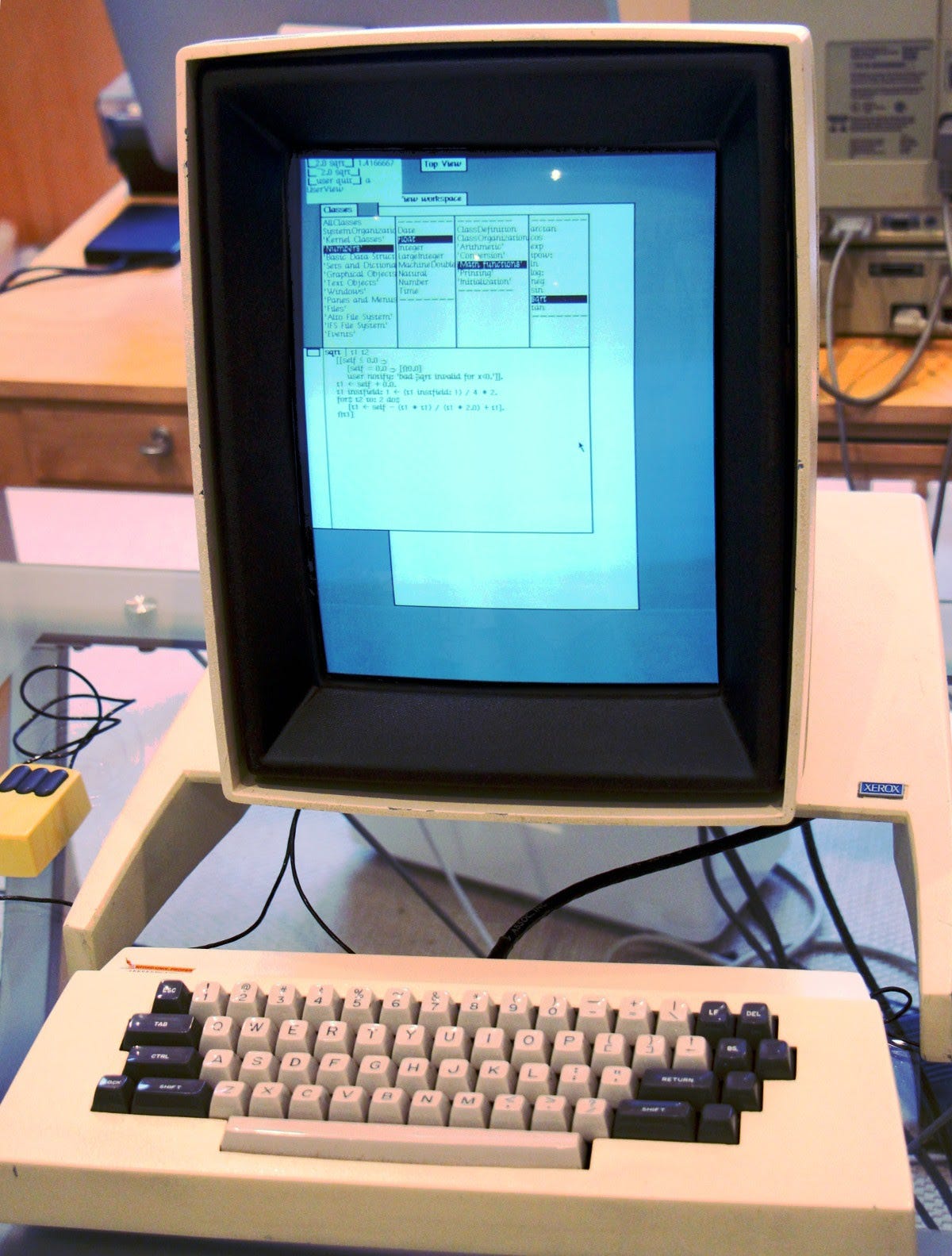

[Bob] Hi, welcome back to Operation Code Podcast. I'm Bob Purvy, and our guest today is a little different than the usual. Dick Sonderegger learned computers in the Marines back in the 1960s in the Vietnam era, and I actually shared an office with him for a while at Xerox and reconnected recently. And we thought we'd talk about what things were like back then and what his 50 years in the computer industry has taught him. So hi, Dick. How are you doing today?

[Dick] Just fine, sir. And you?

[Bob] So my Operation Code homies had a question here, which I know the answer to, but I'll ask it anyway. It's “what did you study in Harvard and did you use the GI Bill to finance it?”

[Dick] Well, I went to Harvard twice. The first time I was a member of the class of ‘68 and I was at Harvard on a full Naval ROTC scholarship. and my major at that point was medieval history. My father was a professional historian. History always interested me and somebody told me that a history degree would be good for a lifelong career in law and I figured, oh, that'll be cool. So, sophomore slump, and I flunked out and wound up in computers in the Marine Corps. Four years later, I applied for readmission, and they accepted me, and I immediately changed my major to applied mathematics. There was no computer science degree at Harvard at that point. All of their computer courses were down inside the applied mathematics department. So the degree says applied math, but it's a computer science degree.

[Bob] I did kind of the same thing myself at Illinois. So how did you get into computers then?

[Dick] Well, as I said in my email, you go to Parris Island. When you withdraw, when you drop out of a college and you were on a Naval ROTC scholarship, you don't get to walk away. They've got you, and they've got you for four years. So I had a choice. I could either go into the Navy or go into the Marine Corps. And for some reason, at that point, I wanted to become a pilot and go fly close air support. So the Marines would actually make you a pilot without a college degree. So I got dressed up and went down to the customs house in Boston, which is where the Marine recruiter was, and introduced myself and said, hi, I want to join up. And there was a grizzled gunnery sergeant, and he stood up and he said, no, you don't understand. You go back to Cambridge. Go back to Harvard Square where you belong. I never want to see you again.

[Bob] Wow. I thought he would say, hello, sailor! Sign right here.

[Dick] So I went back to Harvard Square. I said, you know, what on earth do I do now? And so I waited a day or two, went back down. It was a different guy. I tried to explain to him, I said, look, you know, I really have to do this. And the Marines are where I want to be. And you're it. So sign me up. And, oh, about six weeks later, I was on a train headed for Parris Island.

So you take all the tests at Parris Island, and they figure out what it is you're good at, right?

[Bob] I'm going to stop you here. So did the pilot thing not work out? You weren't pilot material?

[Dick] Well, the first thing that happens is they give you an MOS [military occupational speciality], right? And so I sat down in a conference room or in a small office across the desk from a corporal, not much older than I was. And he told me, you scored perfectly on the logic test and you scored perfectly on mechanical aptitude. So you can either go to computer school and be a computer programmer, or you can go to the motor pool, be a mechanic.

[Bob] Well, hell, I’d go to the motor pool in a second.

[Dick] Which is exactly what I told him. I said, man, I love trucks. The motor pool is for me. And he came out from behind the desk, grabbed me by the throat, and he said, you idiot. You have no idea what you're talking about. You're going to be a computer programmer, and you're going to like it. And he set me off.

[Bob] So I guess you don't fight with that. You just salute and say, yes, sir.

[Dick] Well, I went back and figured I can still go to OCS. And so I went out and put together all of the paperwork for an application to Officer Candidate School. And the very last piece of that was an interview. And so it's now, I don't know, we were probably six or eight weeks into Parris Island. When I went through, it was a 10-week course. And so I got a notice that I should be at a certain parade ground, drill field, at a certain time. And I went there, you know, out in the middle of this mammoth parade ground. And all of a sudden, this first lieutenant showed up, and he says, I'm here to interview you for OCS. And why do you want to be an officer? And I said, well, sir, I want to be a pilot. I want to fly close air support.

And he got right absolutely in my face. And he was probably all of 5'6", and I'm only 5'8". And he starts screaming at me. and said, what is wrong with you? Do you have a death wish? You have no idea! And I remember looking down at him and saw on his chest the Ranger insignia and parachute wings. And the only thought I had was, he's talking to me about a death wish? What's wrong with this picture?

[Bob] So it wasn't that he was actually looking out for you. He didn't think, oh, this guy can't do it. He thought, I'm going to give this guy a break.

[Dick] Absolutely. So I forget the rest of the interview. It's all kind of a blur. And I really don't know what happened next. The information I got at Parris Island was that I'd been approved and the application was pushed up through the pipeline. By the time, oh, probably another, I don't know, three or four months went by. And by that time, I'd gotten orders that they were going to send me to programming school. And the people at the company office told me, oh, your application's been lost. You have to do it again. And I sat down and I thought about that. And I thought, that's probably not a good idea. The rest is history.

[Bob] So the application to be an officer had gotten lost. Is that what you mean? Okay. So I think our audience, some of whom have either been in Parris Island or at the Hollywood branch of it in San Diego, are going to be highly amused by this. So I think you're the first person who's been ordered to go into computers that I've talked to.

[Dick] It clearly was the best thing that ever happened to me, without a doubt.

[Bob] So if you'd been in close air support, we might be talking to you about you as the late Dick …. Well, never mind.

[Dick] Exactly. It's probably tough, too.

[Bob] So tell me about the programming school. What did you learn in that?

[Dick] So it turns out that they had picked thirty Marines to do the implementation of this joint uniform military pay system [JUMPS]. This was, oh, what? So this would have been fall, late 64, early 65. And they finally got us all together in February of 65. It turned out that there were 30 people, and the entry, if you will, was you had to have certain scores on that logic test, whatever. And you had to have at least 18 months left to do in your enlistment. And so there were college dropouts from all up and down the East Coast. The next thing we found out was that all the services had been directed to implement this joint uniform military pay system. And the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy, of course, didn't let mere enlisted men do anything important. So all of their implementation was going to be done with officers. We were told that the Marine Corps really believed in enlisted men, and we had two officers who were going to be the system designers, and all of the implementers were going to be enlisted men. So each service had its own team on this joint? We being fresh college dropouts, we were all corporals and below. late teens, early 20s. But so they picked us up, sent us to D.C., put us up in an abandoned, almost condemned barracks just up the hill from the Pentagon and enrolled us in programming school at the IBM Education Center in downtown D.C. So every day we got however I mean most of us had cars and what not got ourselves into downtown D.C. spent the day at the Ed center doing learning COBOL at that point and then everybody at the end of the day headed off to whatever their part-time job was.

[Bob] Oh, you had an outside job, outside the service as well as in?

[Dick] Oh, absolutely. Well, they didn't pay us enough. What are you, kidding?

[Bob] What do I know?

[Dick] You know, this was 1966, ‘67, right? So I had grown up on the water, sailing on Lake Superior. So I got a job down at the Capitol Yacht Club right in downtown D.C. where all of the muckety-mucks parked their yachts. Five or six other guys got jobs as bouncers at a bar in Georgetown. So this became the Marine and Marine Corps Programmer Bar in Georgetown.

[Bob] I had no idea about all this stuff. I figured once you were in the service, that was all you did.

[Dick] Oh, no. Well, like I say, there at that point was a Navy facility on Columbia Pike, just up the hill from the Pentagon. And there were some officers there. There was a mess hall, the small commissary. It was just down the hill from Headquarters Marine Corps. And there was no room for us at Headquarters Marine Corps. And there were these barracks that were no longer being used on this Navy facility, Quarters K. So they put 120 of us in a barracks, or they put 30 of us in a barracks designed for 120 people and said, “Here, you know, you can get meals at the Navy mess hall. And every day you have to be downtown at the education center by 9 o'clock. See you later, bye. “

[Bob] So how long did the course last?

[Dick] Oh, man. Started in March, went to the end of August.

[Bob] Okay.

[Dick] And so I got married in mid-August, and by Labor Day, you know, she and I were in the car. I had orders to go to Kansas City. And it turns out there was a Marine Corps finance center in Kansas City, and that's where this implementation was going to be done. So we all wandered off to Kansas City. And, of course, that was temporary additional duty also, right, because there's no Marine Corps barracks or anything in Kansas City.

[Bob] So where did you stay out there, then?

[Dick] She and I were able to rent an apartment across the street from the finance center, a little garden apartment complex. And most of the other folks kind of rented apartments here and there. Those who were single, they would put two or three to a two or three bedroom apartment. I'd say probably by that time, half of us were married. And so it was in Kansas City until March 1970.

[Bob] Wow. So this was a payroll system, right?

[Dick] Payroll and personnel. So the notion was to get all the services off their card-based 1401 systems

and get onto – well, I know that the Marine Corps system was all IBM-based. latest technology for the time, but, you know, direct access storage, video display terminals. And so the personnel part of it was all pretty much, you would recognize it today as an online, real-time personnel system. And then the payroll system took changes from that personnel system, applied them to the personnel database, and all of the kind of standard things that you would be used to in a card-based payroll system, now were all done on shared storage. And really the only thing that was external was the paychecks themselves.

[Bob] Little space-age stuff, huh?

[Dick] It really was. Like I say, this was now into ‘68, ‘69, and I got out, end of March 1970, went back to Harvard, and in reality, I got through Harvard on the stuff that I learned implementing the JUMPS system.

[Bob] But I think before we started this conversation, I mentioned to you that at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, there's a working 1401. And I just saw it last week. The guy who restored it, Bob Garner, has also restored a couple of mainframe 360s. I'm hoping to get him on later. I asked him if he had any questions for you, but I asked a little bit too late. So tell me about, I think, for our users who are used to having 16 gigs of main memory, how much disk space did the system take up?

[Dick] What, the 1401?

[Bob] The JUMPS system.

[Dick] The JUMPS system, what was there? Those guys were 300 megabytes each, and there were 16 of them.

[Bob] Okay. That's pretty big for its day.

[Dick] Yeah, yeah. So the fast disk was the big 300 megabyte disk packs, and each unit had eight of these packs in one monolithic unit. Huge. And then the slow stuff was an absolute Rube Goldberg thing called a data cell.

And imagine a tall pie-shaped container containing strips about the size of an IBM card and twice as long, right? and contained those strips vertically. And the strips were made out of magnetic tape material. Okay? And so you would address a specific strip card and then a strip on that card. And the mechanism would come along and reach down into that pie-shaped container, grab the strip, pick the strip up, wrap it around a cylinder, and then there were heads that would play back and forth across the strips.

[Bob] So the access time was in the seconds, I'm guessing, right?

[Dick] Oh, yeah. Rube Goldberg, you betcha. The only thing that people would claim was that the system really was quite intelligent in that it would understand when a strip had reached the end of its life and when the strip was going to be put back down into the pie-shaped container, it would go off-center and it would just crumple the strip up and destroy it.

[Bob] So did that ever happen by accident? I'm curious. It must have.

[Dick] It was astonishing.

[Bob] I don't think I've ever seen one of those, actually. I don't think – if they have one at the Computer History Museum, I didn't see it. They had this one disk unit that had about 30 platters in it. I'm not sure what that was.

[Dick] I can remember going to the History Museum when it was in Boston before it moved out west. And I don't think I saw a data cell there either.

[Bob] Too funny, too funny. Let's see. By the way, I'll ask the last of the questions from the Operation Code people, and then we'll get on to other stuff. So question three was, by the way, I'm not responsible for this. Has anyone ever mispronounced your name as Schrodinger?

[Dick] Not as Schrodinger, but they've mispronounced it a whole bunch of other ways. And I don't have any cats anymore.

[Bob] Actually, it was fairly easy to find you on LinkedIn because it's not a common name, just like mine isn't. So after the Marines, you went to Harvard, and then you were at Data General.

[Dick] true yep

[Bob] and I think you mentioned Soul of a New Machine. Did you, I forget the guy's name, Tom was it, Tom West, was that his name?

[Dick] Right yeah yeah

[Bob] Did you know him?

[Dick] Tom West. Quite a bit. Nice guy.

[Bob] But was his life changed by the book or or not so much?

[Dick] It was interesting. The book came after I had left Data General. The book came, you know, really while you and I were there in El Segundo. But so I talked to several of the people who had been interviewed by Tracy Kidder during the time of the book, and they did not have flattering things to say about Tracy Kidder. I can remember, I read the book absolutely as soon as it came out. And when it was done, I put it down and my comment was, I don't get it. This is a historical novel. Okay. This is, this is not what really happened.

[Bob] That's funny. That's funny. I'm the reason I actually got in touch with you is, I'm writing a historical novel about Xerox Star, except I don't claim that it's actual history. Like he did claim.

[Dick] Well, I'll tell you, the guys that I talked to at Data General who have been the interviewees of Tracy, to a man, they said, you know what? He didn't know anything. We could have told him anything, and he would have bought it. We twisted him around the axle more times than you can count. And from reading the book, yeah, that's accurate.

[Bob] That's funny. At least I – so you and I actually did share an office together at Xerox for a while. I don't – how – a few months was it? I don't remember.

[Dick] Yeah, I think. It was while we were upstairs on the second floor.

[Bob] Okay. And I actually – I guess you moved – we separated in, what, 1978 or something, was it?

[Dick] Yeah, I think, about that.

[Bob] I don't, I actually, if you told me you had left Xerox then, I would have believed you because I don't remember ever seeing you after that. I'm sure I did.

[Dick] Well, I can remember going downstairs to the first floor. And about that time, I wound up as the manager of the support arm of SDSupport. And I think you stayed in Development.

[Bob] Yes. So what do you recall of the Xerox effort?

[Dick] It was an interesting time. I got hired because I had done a fair amount of work with photo typesetters and had put together a text formatting and photo typesetting program while I was at Data General.

[Bob] Okay.

[Dick] And so all of that arcane typesetting vocabulary made sense to me.

[Bob] Now it comes back to me. I was trying to remember what we ever talked about. I don't know if I even knew you were in the Marine Corps. Did I? Well, I always make a point of saying here in Operation Code, I didn't serve, myself. I'm serving now.

[Dick] There you go.

[Bob] But a lot of people back then, you went to a lot of effort not to get in the military.

[Dick] Yes.

[Bob] And I feel sort of embarrassed now to be around all these people that volunteered for it and did it. But, you know, I can't change that.

[Dick] A long time ago. But so about the time that they split the offices up, if you'll remember, the development environment and the infrastructure really was just falling apart. And I can remember at one point I finally being frustrated with something wrong with my Alto

or whatever and went to – I forget who I went to see. But one of the managers, either one or two levels up in the organization, and just read him the Riot Act. “This is absolute bullshit. Our infrastructure is falling apart. Nothing works. We can't get anything fixed. And how are you going to build a system when the infrastructure won't stay together for a day?”

[Bob] And what was the answer?

[Dick] His response was, you know what? We've been looking for somebody to manage that group, and you're it. And I can remember walking back out of the office saying, I don't know if this is a good thing or not. yeah but they um I said well you know I need folks to work with and they said, well okay, you know, they gave me I don't know I think six head counts and a list of the technicians that were over working for, oh, Abby. Anyway, who were working on the assembly line, putting together the Altos, okay? We were able to really bring things back from the brink. And I think, I hope that you'll agree with me that the infrastructure didn't get repaired overnight. but it did get repaired.

[Bob] It's kind of interesting. I mean, one of the, just as a commercial for my novel, I mean, one of the basic questions is, why did people put up with this stuff for so long? Especially when, I think, I've talked to some people now, and what did we think at the time? And I think what people thought was, well, this is really incredible technology, and I guess I'm going to stick around and see what comes of it.

[Dick] Well, and really, when it worked, it was magic

[Bob] Yeah yeah you know there's there's a guy now that has the Star software running on modern hardware and I haven't seen this, but I'm told it's just grease lightning fast too.

[Dick] Oh lord, well I still remember you and I are sitting here talking over Skype 3,000 miles apart. Okay? And I still remember the day that I was up in Palo Alto and got called into, somebody reached out in the hallway and said, hey, come in here, you've got to hear this. Right? And there were four or five people clustered around an Alto, and there was this disembodied voice. Right? And the occupant of the office was carrying on a conversation with this disembodied voice. I said, what the hell is this? Who's that? And gave me a name of somebody that we all worked with and recognized. And I said, what's going on here? And they said, these packets are coming over Ethernet. That guy's across the street in Coyote Hill. And so these were Pup packets, right? Pup universal packets with an encoded voice going back and forth over a one megabit Ethernet.

[Bob] Yes. Yeah. There's actually an incident that I found out from Bob Garner about when the lightning hit. Do you remember that?

[Dick] Yep.

[Bob] You were there.

[Dick] Oh, my God. I was there. Let's talk about this. Were you involved in, for our listeners, I don't know what we're talking about. this was 78, I think.

[Bob] Yeah, that's about right. And they had an Ethernet running underneath Coyote Hill Road, I think between the PARC building and System Development Division. And there was a lightning storm, which was not very common up here in the Bay Area. And all the Ethernet transceivers were blown out. And I'll let you tell the story if you remember more of it than I do, because I'm sort of going by what I've heard since.

[Dick] Yeah. Well, the strike hit at the top of Coyote Hill Road, so probably a couple hundred yards from the main PARC building. And all the network went out. And people are sitting here going, well, what happened? What the hell was that? Right? And it took them a while. Chuck Thacker and Ed Taft, I think, were two of the main troubleshooters. But you have to understand, Ethernet at that time was a half-inch thick coax cable, right? And the transceivers, the things that connected what we now know as a network interface card, right, NIC, to this Ethernet were probably things about the size of a beer can, that tapped into this coaxial cable. And so there was a vampire tap. This was all community antenna TV technology. But there was a vampire tap that went into the Ethernet, and that's how the signal got carried. All right? So then they started finding, lo and behold, that all these Ethernet transceivers were fried. And they went back and they looked at it again and again and realized that as the Ethernet went into the conduit underneath Coyote Hill Road, these bare transceivers, I mean, they were just Bud cans, right? There's no insulation. They were sitting on the conduit as it went under the ground, right? And so the lightning strike came along, and now all of a sudden you've got a ground loop going from the top of Coyote Hill Road down to the end of the conduit there by the PARC building, running through the metal conduit over to the SDD building, and then back up to the top of Coyote Hill Road.

[Bob] So what I've heard is there was a wrench sitting some place that provided connectivity?

[Dick] Yeah, that could have been. All I heard was just through the coax or through the conduit and a ground loop. But every transceiver that was just sitting in the conduit, right,

[Bob] And supposedly this was like the day before the Xerox executives were supposed to fly out and see a demo? Naturally?

[Dick] That, I don't remember.

[Bob] What I've also heard was, it was grounded in two places. And because of the lightning, the ground potential was different in two places.

[Dick] True statement.

[Bob] This is so funny. I didn't realize you were there.

[Dick] Oh, absolutely.

[Bob] So this is going to go in the book for sure. And I was there. I don't remember it at all.

[Dick] But it was something. And the whole process to bring the network back up was a couple of days.

[Bob] So there's a video where Ron Crane talks about that.

[Dick] Really?

[Bob] He said he replaced the transistors in all the transceivers.

[Dick] Oh, man.

[Bob] I guess they were discrete components back then.

[Dick] Oh, yeah. Yeah. Discreet components, transistors, chokes. I mean, yeah, this was old time stuff.

[Bob] Oh, man. So let's see. So I lost track of you after Xerox. So you went back to the East Coast and….

[Dick] Went back to the East Coast. I was aiming to get to Massachusetts, but wound up in Connecticut. Went to work for a small outfit in Fairfield that was making 2.5D CAD/CAM systems, so electronic drafting systems.

[Bob] Didn't you, I have this vague memory, you mentioned you worked for Ivan Sutherland,

is that, am I imagining that?

[Dick] I didn't work for Ivan. It turns out that my wife had been friends both with Ivan and with Bert at Bolt, Beranek and Newman, and we had a Christmas party. We were living in Santa Monica and had a Christmas party and invited, you know, Xerox friends. And my wife was working for USC's, the ISRI, Information Sciences Institute, and a whole bunch of people. And Ivan came. He was working for RAND at that point. And he came and... wonderful guy. And the party went on for hours. He's sitting there telling computer graphic war stories, right? And all of a sudden he said, I looked at the time. I got to go. And I forget who it was. One of the people we worked with at Xerox, you know, who was that? So that's what I thought. He was absolutely mortified that he hadn't had a chance to shake his hand and find out who he was.

[Bob] Oh, man. So let's see. I guess the question, just to make this more relevant for people listening who are now serving in Afghanistan or something and thinking, what the hell am I going to do when I get out? What would you advise somebody like that to do?

[Dick] Part of it, I suppose, is find your passion. You know, if something in the computer industry attracts you or if you, you know, been working with computers while you were in. Right. As I said in one of my emails, I'm a real fan of getting a good, solid, theoretical grounding. And once you have that good, solid theoretical grounding, you can take that real-life experience that you've gained and parlay that into … who knows. So I wound up at Data General just by chance. I was sitting there at the first meeting of a course in the fall at Harvard. The instructor came in and said, one of my friends works in the publications arm of Data General, and they're looking for somebody to come help them document a new computer. And I can remember sitting there thinking, well, yeah, I can do that. I thought the various IBM documentation was just awful. I could do a better job. And it took – I couldn't get out to Southboro for a day or so. And I figured, well, the job will have to be gone, but I'll call the guy anyway. And called and went out. We had a nice talk, he gave me a copy of the current Data General, you know, Programmer's Reference manual and said, “Why don't you read this and tell me what you think?” And I took it home and I read it and it was awful. It was awful. If I remember one of the things that just drove me nuts, there was a description of the front panel of the original Nova computer. and one of the lights on the front was the run light, okay? And the description of the run light was, when the run light goes out, the computer stops.

[Bob] Technically true.

[Dick] Well, technically, but the cause and effect is wrong, right? So I went back out, and he said, “now tell me, what do you think of that?” And I said, well, I'm really sorry. I think it's wah, wah.

[Bob] It's hard to know when to be diplomatic and when not to be.

[Dick] Absolutely. I couldn't agree more.

[Bob] That's so funny. I mean, one thing that impressed me about Xerox manuals was that they actually look like publications. They had upper and lower case and the margins were justified and …

[Dick] Oh, yeah yeah yep. Well and so, we were putting this stuff together when we had, really for the time, fairly good publishing technology and you know IBM executive typewriters which were variable width, and we had a couple of Selectrics with some variable width balls on them. But after a while, I and another colleague of mine were able to put together this typesetter system, right? Using a typesetter that, how do I put it? This typesetting company bought Novas to put down inside the typesetter, right? So we bought one without the Nova, managed to cobble together a Nova, put inside it. Now, lo and behold, we had a running typesetter for cheap. But now we were able to put together real, honest-to-goodness typeset manuals. And what we found out was if we took one of these typeset manuals and put it out for review, right? No one would mark it up. No one would say that they thought there were any errors in it because it looked wonderful. And we found that the only way that we could get people to actually sit down and write comments was, we would have to print a copy on a typewriter.

[Bob] Well, yeah. There is the effect of just having lots of fonts, which I think people have outgrown. But it used to be that you took every font you had and used them all because they were there.

[Dick] Oh, yeah, absolutely.

[Bob] Oh, God. So we've been about 40 minutes now. But what the hell? Was there anything else you wanted to talk about?

[Dick] Whatever floats your boat. We've gotten to Data General. There's a whole bunch of computer industry after that.

[Bob] Yes, there is. So now you're in – I don't really know what DataLink does. It has to do with storage area networks.

[Dick] Yeah. DataLink has gone through several different transformations, but they've always been kind of a data center equipment and services company. Right. So when I went to … they bought the company that I was working for. We were storage technology, OEMs, and quantum OEMs. We would sell data center equipment and service it. So DataLink bought MCSI. DataLink had many more computer partners. And so they could sell all the stuff that you would find sitting in a data center computer room. Shared storage, backup systems, tape libraries, servers, you know, all of that. And I just really resonated to it, more toward putting together fiber channel storage area networks than putting together server farms. But, I mean, you know, everybody kind of responds to their own piece of the pie.

[Bob] Anyway, Dick, it's been great reconnecting with you.

[Dick] And the pleasure has been mine. Thank you very, very much.

[Bob] Okay, this has been Dick Sonderegger. I'm Bob Purvy with Operation Code, and I want to thank Dick for taking time out of his schedule to talk to us. Tune in next week when we talk to Mike Rodriguez, who was also in the Marines and also had the choice between computers and motor pool plus HVAC, but in his case, he chose computers. Okay, for Operation Code, bye-bye now.

[Voice] From all of us at Operation Code, We want to thank our listeners for their continued support, as well as every member serving in our armed forces. Our country and world are much safer because of the work they provide. Please show your support or learn how we can help you transition into a software development career by joining us for free at OperationCode.org. Help us deploy the future.

[music]

[Bob] That was Buddha Blue provided by the U.S. Army Blues Band recorded live at Blues Alley in New York City

Afterword

My book has been out for a while now. I made that lightning incident into its own chapter, different from the facts only in that my fictional characters play a part in it.

Ron Crane, RIP, was the real “Tim” character, who figures out what happened. I don’t know if I’ll ever get a better moment as a writer than I got from his widow, so said I captured his personality perfectly and she hadn’t thought about him so much since he died.