This is a beginner’s guide to the recent story that “Google Ads” is an illegal monopoly. If you were thinking, “well, ads are ads, and now they’re history” this will set you straight. On the other hand, if you’re really expert on this topic, you’ll probably find things to quibble with.

Judge Leonie Brinkema ruled, as the New York Times headline says, Google Is a Monopolist in Online Advertising Tech, Judge Says. So if you still believe the mainstream media, you think, “Wow, their whole business is now illegal! Sell the stock!”

I worked in Google Ads for about three years, so let me explain what the case was actually about. It’s not about those ads you see when you do a search.

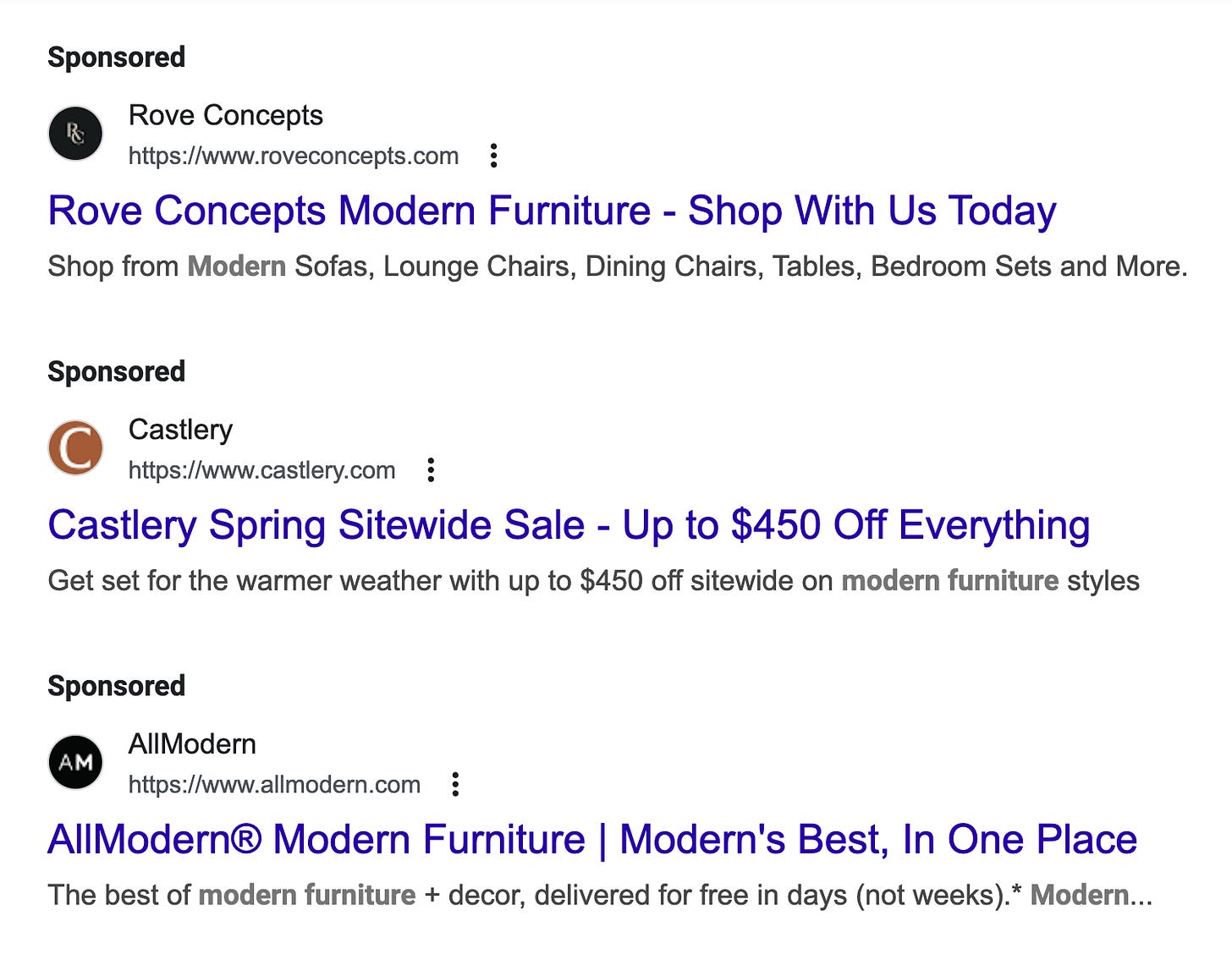

Search Ads

Those are the old-fashioned text ads. Nowadays, they can be fancier:

They’re still ads that presumably show you what you were already searching for (modern furniture, in this case). That’s called “intent” in the ad business; just what the advertiser wants if they’re going to pay to show it to you.

When you see an ad for Ford F-150 trucks on TV, you may or may not have any intent to buy a truck, now or ever. Maybe you can’t even drive. Still, Ford is paying to show it to you.

An ad for something is worth more if the viewer has some intent to purchase it. A lot more. Furthermore, the Google magic is that the advertisers only pay for those ads if someone clicks on them. That’s what made them a trillion-dollar company.

Display, or “Content” Ads

Here’s the other main type of ad, which we generally call a display ad.

When you go to wsj.com, the advertiser pays to show you that ad, whether you want to see it or not. This is paying for impressions, not for clicks. That’s what Judge Brinkema’s opinion was about, not the Search ads.

There is a massive Google infrastructure for selling these display ads. I’ll show the judge’s diagram of it below. The infrastructure is:

for content owners to sell their space to anyone who wants to advertise there

for advertisers to place their ads in the spots they think will be the most effective

to allow those two sides of the transaction to meet and settle who gets to advertise where.

If you have a website that attracts traffic, you can devote a portion of it to ads and sell it through Google (or its competitors, which was what the lawsuit was about). You don’t need ad salesmen out pounding the streets, like Herb Tarlek on WKRP in Cincinnati

Where’s the Money?

I said that Search ads were more valuable than display ads. Now we’ll see how much more. Here’s Google financial results for the last quarter of 2024:

Let me single out two numbers in particular for the last quarter of 2024:

“Google Search & other”: $54 billion

“Google Network”: $7.9 billion

Judge Brinkema’s decision was only about the second one (Google Network). It doesn’t touch the big gorilla: the search ads ($7.9 billion per quarter is not small change, of course).

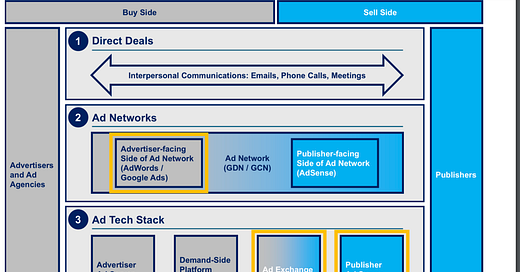

Here’s the diagram of what was at issue in the suit:

The “sell side” is the publishers wishing to sell their ad space. The “buy side” is the advertisers and ad agencies wishing to buy it.

The publisher lists their space and their pricing guidance on the “Publisher Ad Server.” The advertisers list their requirements and pricing offers on the “Advertiser Ad Server” and “Demand-Side Platform.” They meet on the Ad Exchange. Believe it or not, an auction happens in real time, as the web page is being displayed! The advertisers place their bids and instructions on how to raise them, the publishers place their offers and instructions on how to lower them, and an auction resolves it, or fails to.

In theory, then, the publisher gets the best possible price for their ad space, and the advertiser places their ad in the lowest-cost place that meets their requirements.

I’ve oversimplified and it’s immensely more complicated. The judge’s decision is surprisingly readable as a tutorial, if you skip over all the citations.

The judge found that DFP and AdX (the boxes outlined in orange on the bottom) were illegal monopolies under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, meaning that they were monopolies and that Alphabet had acted illegally to create and maintain them. The information about and conduct of the auctions, in particular who bid what, who offered what, and how information was communicated, is immensely valuable to all sides, but Alphabet keeps that very close to the vest. It was also found to have illegally tied DFP and AdX, a legal term meaning you can’t just buy one without the other.

You can read the Reuters faux-objective story on the decision, and an industry newsletter piece that’s more openly opinionated.

What’s Next For Display Ads?

Another ad industry piece explores what might happen. If you’re not familiar with all the jargon (header bidding, take rate, CPM), the judge’s decision is an excellent tutorial.

For all the optimism and sense of gleeful vindication for many in the industry, any actual antitrust remedies will be a long time coming, said Brian Albrecht, chief economist at the International Center for Law & Economics.

For example, the DOJ’s search antitrust trial against Google is entering the remedies phase this week, some eight months after that monopoly case was concluded in August. This case, likewise, could be almost a year removed from finding out what remedies are even being pursued in the ad tech antitrust case, let alone a decision.

Then there would be an appeal. Google has already announced it will appeal against last week’s decision, in addition to the decision in the search antitrust trial. Those appeals can stretch for a year or more.

And Google might win a reversal.

According to Albrecht, the ruling could be vulnerable on appeal, based on recent Supreme Court precedent in antitrust cases that requires proof of harm on both sides of a two-sided marketplace.

In other words, don’t hold your breath waiting for any immediate changes.

That Other Trial (Search)

I showed those two numbers above: $54 billion for Search and $8 billion for Display. As you’ve probably read, there is another trial going on that does touch that $54 billion Search revenue, and that is US District Court Judge Amit Mehta’s trial.

This deserves its own post, so I’ll say more about it later. But just for fun, here’s the gross, general formula I remember for RPM (revenue per thousand queries). RPM is a fairly “noisy” number, and experiments are usually aimed at more narrow metrics, like CTR (click-through rate) and usually even narrower than that.

RPM for search ads =

(# search queries x

percent of monetizable queries x

average click-through rate x

average cost per click)

Divided by 1,000

Even this is an approximate, because we should factor in the number of ads per query result, and also that the user can click on multiple ads. Let’s not be pedantic.

Let’s focus on “percent monetizable queries,” There have always been some queries that no advertiser wants to advertise on, or is allowed to, e.g. “how to build a bioweapon.” But some are purely informational, too. Google doesn’t make the MBA mistake of ignoring those in favor of high-value queries, e.g. travel, entertainment, shopping. It serves them all, in the hopes that you’ll always go to Google no matter what your query is.

If “percent monetizable queries” can be increased, that goes straight to revenue. It appears that they’ve been energetically working on that since I left. I asked Gemini (Google’s AI system) for some examples of queries with no ads, and this is what it came up with:

You got it! Here are some example queries that often return with absolutely no ads in the search results right now:

"what is the capital of nepal": This is a straightforward factual question.

"how to say hello in icelandic": This is a specific language translation query.

"what is the chemical symbol for gold": This is a basic science fact.

"current time in tokyo japan": This is a real-time information query.

"easy recipe for scrambled eggs": While food-related, this basic recipe often doesn't trigger ads.

"poem about a bluebird": This is a creative, non-commercial search.

"what is the definition of photosynthesis": This is an educational term.

"how many sides does a hexagon have": This is a simple geometric fact.

"who painted the mona lisa": This is a well-known historical fact.

"translate buenos dias to english": This is another direct translation request.

Keep in mind that these are examples, and the presence or absence of ads can sometimes fluctuate based on various factors I mentioned earlier. However, these types of informational, non-commercial, and very specific queries are generally less likely to have ads associated with them.

Just for amusement, I tried some of these. Do them all yourself for even more Big Fun.

The Capital of Nepal

How to Say Hello in Icelandic

Who Paid for Those?

If you’re imagining that Google is showing the videos by “Coffee Break Languages” and other creators out of altruism, you may want to look for a Nigerian Prince who needs help getting his fortune out of the country.

In this Google page on how to advertise, they explain how “videos” are one of the modes you can use:

None of this Search revenue is affected by Judge Brinkema’s decision, but if Judge Mehta’s case results in a remedy which lowers “# search queries” that will leave a mark. More in another post later.