Consider the following situations (some imaginary, some all too real):

A group of middle managers at a corporation are tasked with dividing up the money for salary increases. They have to decide which managers will get the money for their groups, and how much.

A state of the US is so unhappy with the politics that it wants to secede.

A Jewish nation in the Middle East is involved in intractable conflict with its Arab neighbors.

A country invades another country. It succeeds in capturing some of their territory but is stalemated in going further. Neither side is willing to back down.

A political party has a presumptive nominee whom many wish to get rid of. It’s asserted that that is impossible; the delegates are already chosen and pledged to that nominee. State laws, in some states, require them to vote for the winner of their primary.

(This last one might have such a short shelf life, events moving as fast as they are, that I’m putting it out now and the last Fremont Older posts will have to wait.)

A Universal Law

It’s the recurring dream of a certain class of people to always have a “law” which just tells you what to do. In their defense, “the rule of law” is one of the cornerstones of civilization. You know you can’t go killing people just because you don’t like them. If you make a contract, there are courts and police to enforce that contract.

However, there are always cases where the law is silent, and then it just comes down to negotiation. Furthermore (and this is where Taleb’s Antifragile comes in), the notion of “law” does not scale to very large units, like the whole world.

Now we’ll go over each of those scenarios and see how the legalistic approach fails.

A management class

At a previous job, I was in a class for managers and soon-to-be managers, and our team was assigned the following task: divide up the pool of money for raises.

The team soon became consumed with arguments about the objective criteria we should use:

Who’s made the biggest contributions to the company?

How do we define “contribution” anyway?

Should seniority count at all?

What about market salaries for similar work? Should those be considered?

What about a limit on the percentage raise anyone should get?

We completely failed to reach a resolution. The intent of the exercise was to teach negotiation. There is no objective formula that could possibly resolve this, unless it’s mechanical, e.g. everyone gets a 4% raise.

“Negotiation” might begin with, “how about if we each identify N star performers in our own group, and decide how much each of those people get? Then we’ll see how much money is left, and do it again?” This would mean some hard bargaining but it would stimulate better ideas, and most likely you’d come out with a solution instead of failing like we did.

Secession

In 1860-61, 11 states seceded from the US. It was claimed that there was nothing in the Constitution forbidding this, but neither was there anything allowing it. It was ambiguous.

The question was “settled” by a deadly 4-year Civil War, or, to paraphrase Clausewitz, “the continuation of negotiation by other means.”

If that situation arises in the future, there is certainly precedent for going to war, but ultimately it would not be settled by a judicial or legislative solution, regardless of that precedent. It would be settled by the populations and governments involved, i.e. “politics” (or “negotiation”) and possibly its continuation by other means (“war”).

The Mideast

You hear endless arguments about Israel’s “illegal occupation” of the West Bank, or whether the Palestinians have a “right of return” to their lands in the current state of Israel, or whether they are “in violation of international law.” Or whose land it is, really. However:

There is no international law that can possibly ever settle this. Don’t even talk about “international law.”

Virtually all land is occupied by someone who took it from the previous inhabitants. Even in Ireland, the Celts were “settlers,” i.e. they were not the original inhabitants. Neither were the Anglo-Saxons or Normans the original occupants of England.

Although in the Americas there were native tribes occupying the land, most or all of those tribes had seized that land from some previous tribe.

It’s thus idle to discuss who “owns” the land, unless there is a system of law governing land ownership which everyone subscribes to. Although legalistic types undoubtedly find this fact unpleasant, it’s ultimately just about power. It was indeed unfair to Palestinians in 1948 that the Jews wanted to establish a Jewish state there. But they did. Bad things happen to a people sometimes.

How does that apply to “negotiation?" It means that discussions of who is “right” are pointless. Unless both parties agree and mean it, there can’t be any peace.

World War I (not Ukraine)

Hah! You thought this one was about Ukraine, didn’t you?

In WW I, Germany had invaded Belgium and France, occupied a large part of France, and four years of pointless slaughter ensued. Front lines moved by yards, not miles. All efforts to negotiate peace had failed. Eventually the combined efforts of British, French, and American troops broke the German army and began pushing it back. The German general staff recognized that they were beaten, and pressured their government to make peace.

In all European wars up to then the victorious powers met, adjusted their borders (obviously in favor of the victors), and made arrangements to ensure that such things didn’t recur. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the Napoleonic Wars,

was an example of that.

The 1815 treaty had more punitive terms than the treaty of the previous year. France was ordered to pay 700 million francs in war reparations, among the largest in history, and even lost territory it had gained during the French Revolutionary Wars as its borders were reduced to those that had existed on 1 January 1790. France was to pay additional money to cover the cost of providing additional defensive fortifications to be built by neighbouring Coalition countries. Under the terms of the treaty, large parts of France were to be under military occupation by up to 150,000 soldiers for five years, with France covering the cost. However, the Coalition occupation under the command of the Duke of Wellington was deemed necessary for only three years; the foreign troops withdrew from France in 1818 (Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle).

There was no “international law” which dictated all this. It was just the outcome of diplomacy, or negotiations. The same would have happened with WW I had events taken their normal course: Germany would have formally asked for peace, the German people would have known they were surrendering, a diplomatic conference would have taken place, and the victorious powers would have done their best to settle things. Europeans were experienced at this. Of course the resulting treaty wouldn’t have worked forever, but then, nothing does.

But here’s where it all went off the rails: US President Woodrow Wilson propounded his “Fourteen Points,” an attempt to establish a universal system of law that would forever prevent another war: Here are a few of them:

1. Open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

5. A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.

14. A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

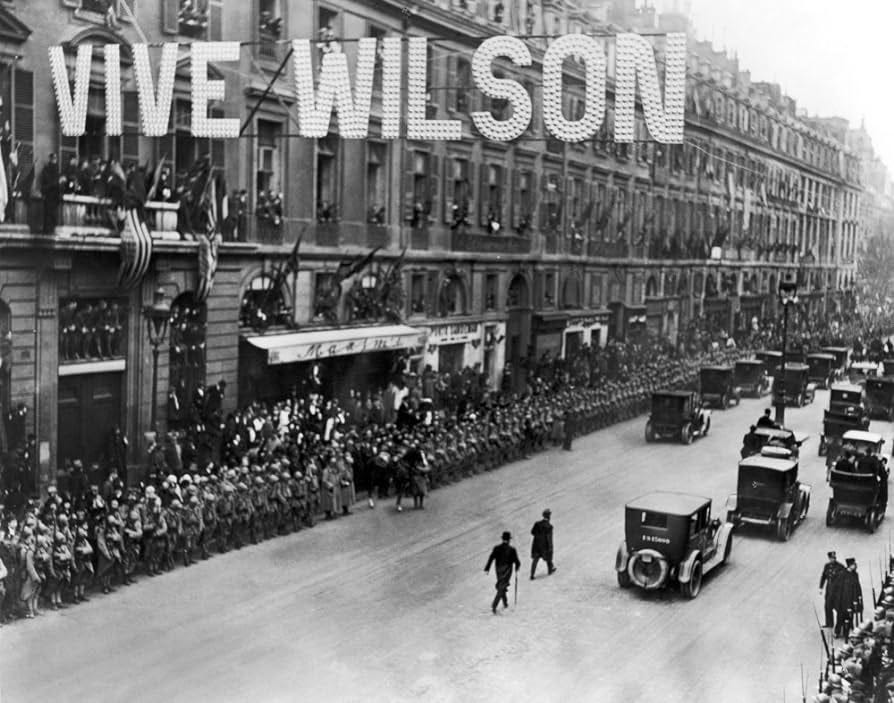

The global effect of the Fourteen Points was electric: Wilson was promising to end all wars. Who could be against that? The US was all-powerful. It could do anything! There was a parade for him in Paris.

The Germans asked for an armistice “based on the Fourteen Points.” Wilson went to Paris in order to bring the Points to the world. England and France paid lip service to them, while privately snickering.

#1 said, effectively: “no more negotiations, except in public.” In other words, “negotiations” needed to become as sterile as a Congressional debate.

#14, in particular, was an attempt to establish a “rule of law” for the whole world. In the Treaty of Versailles, that meant the League of Nations, which fell apart in the 1930’s, and which the US never joined.

mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike

Does this sound like the management exercise we started with, where the group tried (and failed) to establish objective criteria for apportioning the money? That’s what it was and it failed for the same reason: there is no possible universal agreement on what those words mean. World War II happened in Europe because of Wilson and the Fourteen Points, not in spite of them.

Dumping a Candidate

A political party can do whatever it wants. If it had rules, it can change the rules. If you think it’s impossible to dump Biden, you’re just not thinking creatively enough.

This was written before Biden dropped out. The fact that he did proves it was correct. When the party wants you out, you’re out.

Instead of the obvious subject: Biden in 2024, let’s talk about other times when that’s happened.

1912 Republican Convention

Smithsonian Magazine tells the story. Roosevelt had declined to seek reelection in 1908, choosing William Howard Taft as his successor. The two became estranged over policy differences, and Roosevelt challenged Taft in the primaries (which not every state had).

Roosevelt won all the Republican primaries against Taft except in Massachusetts. Taft dominated the caucuses that sent delegates to the state conventions. When the voting was done, neither man had the 540 delegates needed to win. Roosevelt had 411, Taft had 367 and minor candidates had 46, leaving 254 up for grabs. The Republican National Committee, dominated by the Taft forces, awarded 235 delegates to the president and 19 to Roosevelt, thereby ensuring Taft's renomination.

Although Roosevelt had more delegates than Taft, Taft won. The issue was not settled by an abstract law; it was settled by politics. We’ll see that pattern repeated.

On the first day, the Roosevelt forces lost a test vote on the temporary chairman. Taft's man, Elihu Root, prevailed. Roosevelt's supporters tried to have 72 of their delegates substituted for Taft partisans on the list of those officially allowed to take part in the convention. When that initiative failed, Roosevelt knew that he could not win…

Sen. Robert Torricelli

He was a Senator from New Jersey who ran into serious ethics problems, and resigned his seat. He was clearly headed for defeat in his reelection campaign.

In September, two months before the election, the Democrats replaced him with Frank Lautenberg, despite the ballot deadline being long passed. The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that that was legal. Republicans vowed to challenge it all the way to the Supreme Court. Lautenberg was elected.

1972 Democratic Convention

The horror show that was the 1968 Democratic convention led to a “never again” feeling in the party. Hubert Humphrey had won the nomination despite not even entering a primary. It was settled by negotiation among the Party insiders. We should note that, despite Humphrey’s terrible start, he still received 42.7% of the popular vote and 191 electoral votes, to Nixon’s 43.4% and 301.

The McGovern-Fraser Commission set new rules for 1972 (“rules” instead of “negotiation” — does that sound familiar?)

The first guideline ordered state parties to "adopt explicit written Party rules governing delegate selection. It was followed by eight "procedural rules and safeguards" which the commission demanded be applied in the delegate selection process. Specifically, the states were henceforth to forbid proxy voting; forbid the use of the unit rule and related practices such as instructing delegations; require a quorum of not less than 40 percent at all party committee meetings; remove all mandatory assessments of delegates and limit mandatory participation fees to no more than $10; ensure that party meetings in non rural areas were held on uniform dates, at uniform times and in places of easy access; ensure adequate public notice of all party meetings concerned with delegate selection.

Is this redolent of Point One of the Fourteen Points?

The McGovern–Fraser Commission established open procedures and affirmative action guidelines for selecting delegates. In addition the commission made it so that all delegate selection procedures were required to be open; party leaders could no longer handpick the convention delegates in secret.

Ironically, the Convention proved that no matter how hard you try, there is no rulebook that eliminates all politics and negotiations. It still came down to a test vote:

The California primary was "winner-take-all", which was contrary to the delegate selection rules. So even though McGovern only won the California primary by a 5% electoral margin, he won all 271 of their delegates to the convention. The anti-McGovern group argued for a proportional distribution of the delegates, while the McGovern forces stressed that the rules for the delegate selection had been set and the Stop McGovern alliance was trying to change the rules after the game. The credentials committee ruled in favor of the anti-McGovern group prior to the convention, leaving McGovern short of a first-ballot majority. However, the committee was overruled by a floor vote on the first day of the convention and a unanimous McGovern delegation was seated.

McGovern received 37.5% of the popular vote and 17 electoral votes, while Nixon had 60.7% and 520. It’s hard to argue that a traditional Democrat like Humphrey could have done any worse.

So Now: Biden

As I said:

If no one wants you, you’re done.

The Opposite of a Universal Law

The same people who yearn for “the rule of law for the whole world” just brush aside all these failures. “We’ve just got to keep trying!” they say. “Maybe if the US had joined the League of Nations, it would have succeeded!” they say.

No, it would have turned out like the United Nations, at best.

We actually don’t have to keep trying. “Tribalism,” “sectarianism,” “xenophobia” — all those words that are thrown around to scare you: those are good things. Taleb says in Antifragile:

So we exercise our ethical rules, but there is a limit—from scaling—beyond which the rules cease to apply. It is unfortunate, but the general kills the particular. The question we will reexamine later, after deeper discussion of complexity theory, is whether it is possible to be both ethical and universalist. In theory, yes, but, sadly, not in practice. For whenever the "we" becomes too large a club, things degrade, and each one starts fighting for his own interest. The abstract is way too abstract for us. This is the main reason I advocate political systems that start with the municipality, and work their way up (ironically, as in Switzerland, those "Swiss"), rather than the reverse, which has failed with larger states. Being somewhat tribal is not a bad thing—and we have to work in a fractal way in the organized harmonious relations between tribes, rather than merge all tribes in one large soup. In that sense, an American-style federalism is the ideal system.

This scale transformation from the particular to the general is behind my skepticism about unfettered globalization and large centralized multiethnic states. The physicist and complexity researcher Yaneer Bar-Yam showed quite convincingly that "better fences make better neighbors" something both "policymakers" and local governments fail to get about the Near East.

Scaling matters, I will keep repeating until I get hoarse. Putting Shiites, Christians, and Sunnis in one pot and asking them to sing "Kumbaya" around the campfire while holding hands in the name of unity and fraternity of mankind has failed. (Interventionistas aren't yet aware that "should" is not a sufficiently empirically valid statement to "build nations.") Blaming people for being "sectarian"—instead of making the best of such a natural tendency—is one of the stupidities of interventionistas. Separate tribes for administrative purposes (as the Ottomans did), or just put some markers somewhere, and they suddenly become friendly to one another? The Levant has suffered (and keeps suffering) from Western (usually Anglo-Saxon) Arabists enamored with their subject, with no skin in the game in the place, who somehow have a vicious mission to destroy local indigenous cultures and languages, and separate the Levant from its Mediterranean roots.

But we don't have to go very far to get the importance of scaling. You know instinctively that people get along better as neighbors than roommates.

Conclusion

If we drop this silly striving for universal law and world government, what are we left with? Federated government, where we are neighbors rather than roommates. We negotiate things with the other governmental units.

Yugoslavia was a bunch of ethnic groups who hated each other. Tito kept them together as roommates, but once he was gone, it all fell apart, and now each ethnic group has its own country. For that matter, Austria-Hungary was an empire composed of different groups who hated each other. Now they’re in separate countries. Much more recently, the Czech Republic and Slovakia were one country; now they’re two.

Yes, the US is also composed of groups who hate each other, but if you think it’s as bad as the Mideast or the former Yugoslavia, you just haven’t been there. In any case, one group, the Confederacy, did try to separate and were only brought back in forcibly. Oregon and Colorado are much more like neighbors to Idaho and Wyoming than they are roommates with them.

Stop trying to unite everything: that’s the lesson for today.

I started reading, and then couldn't put it down. A rare and thoughtful take on history, highly applicable to the world today.