I’m reposting this, one of the first things I ever wrote here, since, of course, Pope Leo XIV is from this same ‘hood. This is a bit of anti-nostalgia.

I hated grammar school. I hated high school. And I hated living with my family.

So far, this sounds like every other writer’s autobiography, doesn’t it? “I just didn’t fit in, and I was so sad, so buy my book” is how those stories go. But I didn’t get out by writing a novel; I got out after high school, starting with my summer job at Cook Investment Co. in downtown Chicago. (And then I went away to college, but that’s another story.)

My family came from an Irish / Italian / Polish / Lithuanian neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, where your Catholic parish defined where you were from

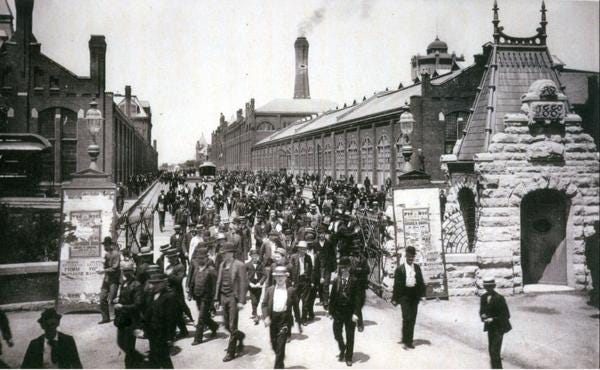

where immigrants and their kids went to work in the factories. This is the Pullman factory where my grandfather worked (also the site of a famous strike in 1894 that became a national issue, and which I’ve written six articles about).

I have no nostalgia for that. Those children of factory workers used to brag about being beaten by their fathers (or their mothers, if there wasn’t time to “wait until your father gets home!”)

When my parents were growing up, children weren’t supposed to have an inner life; they were supposed to obey, listen to the nuns, raise a family (in the ‘hood, of course), and go to Mass every Sunday.

(My first grade class. Amazingly enough, I can recognize some of the kids in here, but I can’t find myself. Maybe we had multiple classes in the first grade? Or I was out that day, or just not in the frame? Anyhow, count ‘em: 50+ kids!)

My parents tried to raise my two older brothers to be like that, but they resisted and got beaten for it. They didn’t like each other much. I did not look up to them like big brothers, and they thought I was a spoiled sissy. Sullen resentment was the usual mood at the dinner table.

Life in the Neighborhood

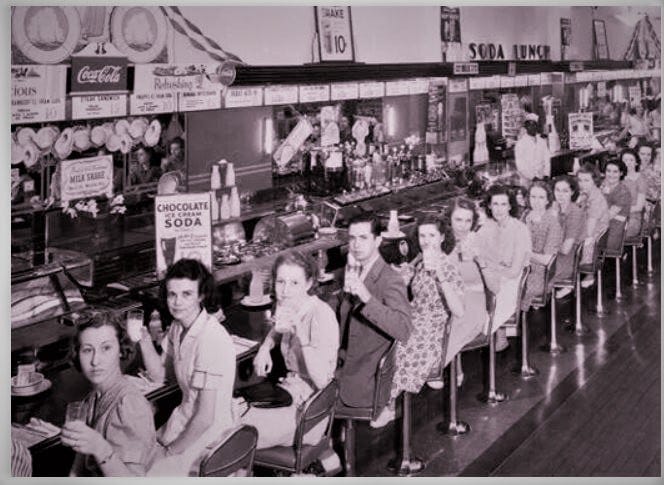

If you see a neighborhood like mine in the movies, everything is warm nostalgia, like this

or this

and kids are always adorable, licking their Slo-Pokes

(All photos courtesy of the Roseland History group on Facebook.)

Maybe some people had a wonderful childhood there and look back on it with nostalgia. I envy them, assuming the nostalgia is not faux. For me, though, these were insular, small-minded people who’d never stick up for someone who was being bullied. They couldn’t even imagine that there was any life outside of Chicago, and more particularly our own little neighborhood. “I peaked in high school” is probably their life story.

There are several “old Roseland” groups on Facebook, and on one of them, a popular post was “What was your. favorite memory of Roseland?” For me, the answer would be “The day we moved out.” (I didn’t post that)

“Michigan Avenue,” which every visitor to Chicago sees, meant something different in Roseland; it meant the shopping street you see in the first picture (with the Gately’s sign). Going shopping meant “going up to the Ave.” Why would you ever go downtown? The Ave. has everything!

As for Italians: my Mom had a lifelong hatred of garlic (mercifully, I never acquired that) because she used to ride the bus with them and thought garlic made you smell bad. She’d always admonish, “No garlic!” I say, “Yes garlic!”

An Alternative Beckons

I didn’t identify with either “bad kid” or “good Catholic boy” stuff, those being the two choices, although “good Catholic boy” was closer. Usually the bad kids were the greaser children of factory workers, and the good kids’ fathers worked in offices. The good kids took Honors classes in high school, so those were my people, to the extent that I had any.

My Dad took me to the Pullman Library every two weeks, and exhorted me to study hard and get a good education and a good job. It was assumed that I was going to college, while my brothers had to be coerced just to finish high school. I owe Dad everything. I might spend an hour at the library looking for books to check out, and he’d wait patiently.

I didn’t stay in the house reading all the time, but I did read a lot. If you saw my previous article about being the cashier at the miniature golf place, you know I took a stack of reading material to work, which probably encouraged the customers not to talk to me. I didn’t want to talk to them, either.

My dad had a best friend Johnny Pollick from before he was married. That’s him on the right in this photo from my parents’ wedding (Johnny was best man):

“Uncle John and Aunt Emily,” we called them, although they weren’t really relatives. They were rich and lived in Glen Ellyn, a prosperous Western suburb, and we visited back and forth all the time. Since my parents knew them before they were rich, there was none of that awkwardness people from different social classes can feel with each other. Their house was larger than ours, but not ostentatiously large. I still have dreams that are set in that house, for some reason.

Uncle John had something to do with the stock market, I knew that much. He didn’t talk about it much. They had two boys, Mike and Marty, the same age (2 years older than I) but not twins.

I didn’t think about that much at the time, but of course they weren’t Emily and John’s biological kids. I loved them all. Sometimes I’d stay at their house for a few days. I think if they’d offered to adopt me, I’d have gone in a heartbeat.

Mike and Marty went to Glenbard West High School, and I went to some school events with them. I was so envious! They had school plays, musicals; they had a beautiful campus; they went on field trips. Once after spending time with them, I wrote an essay for an English class about an imaginary high school I called “Glenlee Township” that had all those things, and one of the other students thought it was silly, because all that stuff could never exist.

You Can Always Go Downtown

When I graduated high school, Uncle John offered me a summer job at his stock brokerage: Cook Investment! It was downtown at 208 S. LaSalle, in Chicago’s financial district

Uncle John had founded the company in 1952 with four other guys, Fred Cook, Stan Baron, Bill Sennett, and Morey (Mo) Sachnoff. He’d been a trader with Swift Heinke, but somehow or other he found the nerve (and the money) to do this, and it had prospered. Stan was the managing partner; he didn’t trade, but he ran the back office.

My brother Jack had worked there full-time before he went into the National Guard. He never considered it a career path, although it could easily have been, and he sometimes referred to it as “Schnook Investment.” The guys at Cook had fond memories of Jack, although not because he used to sneeze without covering his mouth. Whenever I would sneeze, they’d say, “Oh God, here we go again.”

I took the Illinois Central (I.C.) train downtown on the first day. I’d gone downtown before, of course. As soon I had a little money from my part-time jobs in high school, I’d go to Kroch’s and Brentano’s book store on Wabash and buy a bunch of books. If there was any bookstore in Roseland at all, I’d never been in it. The neighbors used to think I was nuts. “Why would you buy all those books?” they’d ask. “You can just borrow them from the library!”

The I.C. cars were very old, had hard wicker seats, and were not air-conditioned (they did get modern, two-decker, air-conditioned cars very soon after that). The train went through the backyards of poor South Side neighborhoods with washing hanging on the lines. The conductor called out the stops, sounding like he had a handkerchief over his mouth, “Roosevelt Road, 12th Street!”

I got off at Van Buren, one stop before the end of the line, and walked west.

The men were all in coats and ties, of course. On really hot days, they would wear “summer suits” made of poplin, but fortunately we weren’t having a heat wave that day.

I showed up in my shirt and tie (I didn’t need to wear a suit, but the tie was expected) and Stan showed me around. It was not a large operation, maybe 20 people in one corner of the sixth floor, facing LaSalle. The trading desk had about 8 guys sitting around, each with a row of toggle switches and a phone. The toggles were dedicated lines to the major brokers, so they didn’t have to dial them. A low partition separated the trading desk from the back office.

Cook was an OTC (Over The Counter) broker, specializing in Midwestern companies. It did not have retail customers, except for a few friends of the partners, and never advertised. Its function was to be a “market maker” in those stocks. If Merrill Lynch, say, needed to buy or sell 100 shares of Anixter for a client, they could always call Cook and get their order filled. They didn’t call for IBM or Coca-Cola or a big stock, since those were on the stock exchange.

We heard the trading desk chatter all day. It went largely like this:

(some trader) “Mo, Anixter!” (In this example, Merrill Lynch needs a quote for Anixter.)

(Mo) “3 1/2, 3/4” (meaning he’d buy at 3 1/2 or sell at 3 3/4)

Assuming Merrill Lynch liked the price, the next call might either be

“Mo, you bought 100 Anixter at 3 1/2,”

or

“Mo, pick up Merrill.” (If it needed more negotiation.)

Cook made all its money on that spread between 3 1/2 and 3 3/4, the bid and the ask. Trading required a quick mind and a canny sense of the market, and Cook had no career path from back office to “trader.” You might get a tryout, but they were not looking for new traders very often. There was only so much room at that trading desk.

The trader would scribble the key numbers on a large white sheet called an “original ticket,” and a typist would create a “confirm” of the trade (pronounced CON-firm) which was mailed out to the other broker. The original tickets were all saved in boxes in a storage room. The confirms were typed up with carbon copies (and I do mean “carbon”) which we saved.

In a day or two, the mail brought us a confirm from the other party, and that’s where I came in: I matched the confirms with our records. If they agreed, I folded their confirm and stapled it to the back of ours. At the end of the day, the matched confirms also went into a box in the storage room.

When you pound a stapler all day, the palm of your hand gets bruised pretty quickly. I used the foot-operated stapler eventually (and broke it, which eventually led to me being nicknamed Mr. Destructo).

Sometimes the confirms did not match, and that was where I had to grow up a little. I’d never been asked to exercise any judgment, like most teen-agers weren’t, but here I was having to solve problems involving real money without being a pain in the ass to everyone. They would explain it to me once but then they expected me to just handle it. Mike Cardin, a senior back office guy, was always patient with me in explaining how things worked, and he told me years later that he deliberately tried to build up my confidence, as he’d done for so many other beginners.

If the confirm hadn’t been mistyped, I’d usually go show it to the trader and get their opinion as to whose fault it was. Most of the traders were nice to me; a few weren’t.

Then I might mail the correction back to the other broker, or as a last resort (my favorite!) stamp “DK” on it (for “we don’t know this trade”). You couldn’t DK things willy-nilly or you’d be removed from your job in a hurry.

Uncle John was one of the traders, of course. He was referred to in the office as “JP” and he suffered from narcolepsy, which led to one guy’s joke “Do you want to see my JP imitation?” Then he’d lean his head back and snore. Usually we’d just smile and move on.

Mike was in his early thirties. He’d been in the Marines, but was not one of those ex-Marines who always have to remind you of it. He recorded the “positions,” which meant that after each day, he’d tally up how long or short Cook was in each stock. He did other book-keeping tasks as well and seemed to know pretty much everything about the company. Mike is still working, in securities regulation, for the State of Illinois Secretary of State’s office.

Cook was a fairly laid-back place, all in all, so Mike used to amuse everyone by calling out to Stan Baron, “I’m under a lot of pressure here, Stanley!” while pretending to wipe his brow. I took Mike as my role model, the big brother I never had.

Stan was also easy-going. I never saw him get angry. Every day after lunch, he’d put on his coat to go out for a walk and say, without fail, “Time to give the girls a thrill!”

Besides matching confirms, I ran errands. This was my favorite part of the job. I’d go to the Continental Bank to get checks certified, to the Midwest Stock Exchange, or sometimes to one of the brokers in the Board of Trade, the big building at the end of LaSalle Street (this iconic Chicago scene is also used in the Brian De Palma movie, The Untouchables):

By Joe Ravi, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15259499

The Board of Trade had “pits”, which were literally pits, with traders standing on the steps yelling at each other and making hand signals

There was the corn pit, the soybean pit, the pork bellies pit, etc. etc. There was a visitors’ gallery above it, where you could stand and watch the action. All the pits have been closed now, as computers have taken over.

I also got an appreciation for Chicago architecture, the best in the world (my impartial opinion) which I’d never learned about growing up. The Rookery, one of the most beautiful office buildings on the planet, was right across the street from us, at 209 S. LaSalle, and there were a few financial firms in there for me to visit, too:

The Rookery was the headquarters of the General Managers Association in the Pullman Strike

To carry stuff, I had an old leather portfolio with a zipper all around it. The zipper was broken so that everything was visible, and once I found out later I’d been carrying $202,000 in negotiable bonds around downtown (“negotiable” means anyone can just walk up to a bank and get cash for it).

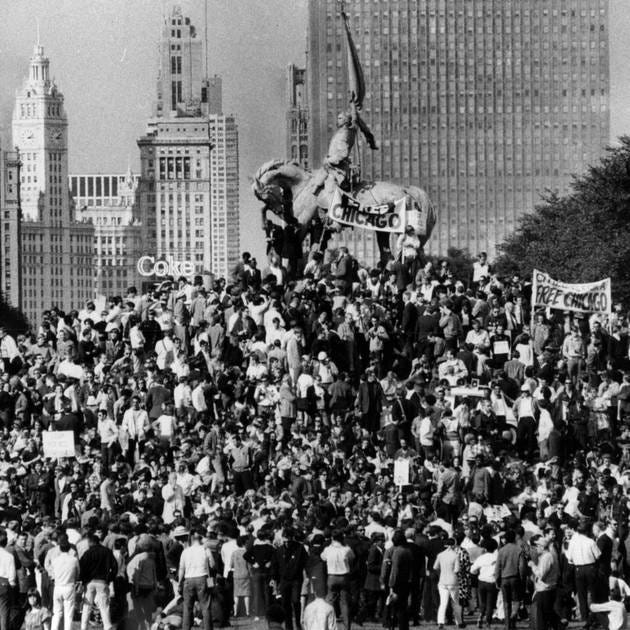

If you’re keeping track of dates, it was summer 1968, and that means the Democratic Convention in Chicago. President Johnson had declined to run for reelection, Bobby Kennedy had jumped into the race but been assassinated, and Vice President Humphrey had the nomination all locked up, despite not running in any primaries (does that sound familiar?). Demonstrators converged on Chicago to disrupt the proceedings and hopefully stop the Vietnam War

We never saw any of this, except on the news. There was violence each night in Lincoln Park, but that was a couple miles from us. The convention itself was at the International Amphitheater, at least six miles from downtown, well beyond marching distance. But the delegates and press were all staying downtown, because that was where the big hotels were.

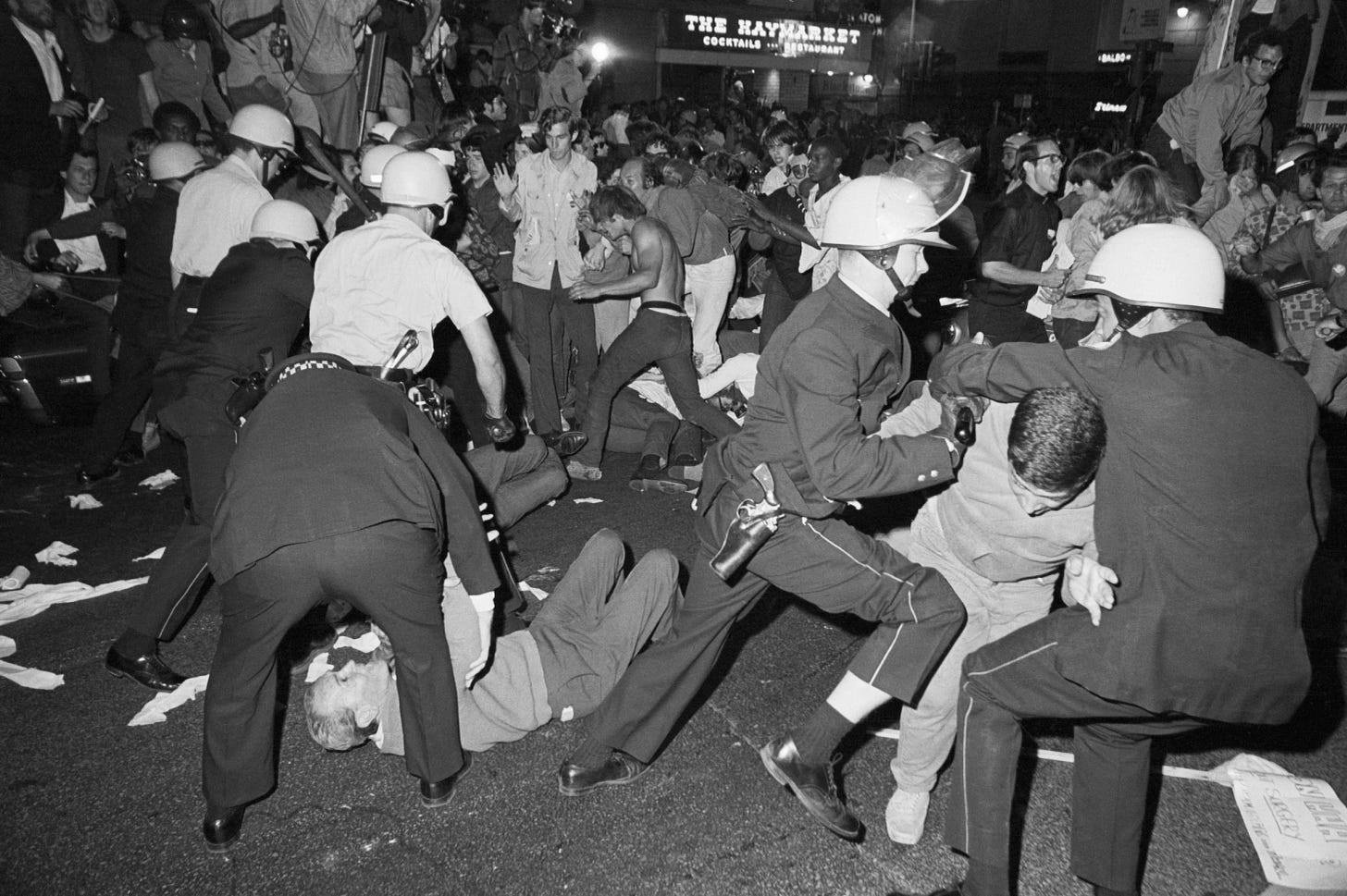

However, my brother Jack (the same one who had worked at Cook Investment before me) was still in the National Guard reserve, and he always got called up when there any sort of disturbance. I don’t think he was ever deployed to the riot area, though, so he’s not in this picture

Wednesday was the big night, when Humphrey was going to be nominated. Everything had been building towards this and everyone knew it.

I gave serious consideration to going to the riot (and we all knew there would be one). However, Jack’s wife was staying with us at the time, and my Mom wanted to pick us both up at the train station at one time instead of making two trips. So I missed getting my head bashed, being tear-gassed, or being arrested. I can only imagine what my Dad would have said about that last one.

Instead, I watched the carnage on TV like everyone else

The next morning, Murph, another summer guy, came in with a big gash on his face (he was not arrested, though). So that was what I missed. It was just another news story for us at Cook; we talked about it for a while and went back to work.

Aftermath

I went off to college. Cook was my first job in an office, and the first time I’d been around adults who treated me as an equal and expected me to act like an adult.

Cook was closed down in the 1980s, as the partners grew too old to continue and wanted out. Mike and another guy tried to buy it with their “sweat equity,” but it was no dice. All the partners are gone now, may their memory be a blessing.

Your beginning reminds me of Ham on Rye Bukowski, just finished it.