Optimism, Hubris, and Strategic Misrepresentation

(Plus a Bias for Action, and Uniqueness Bias) Why Big Projects Are So Bad

In Part I, I explained what a disaster IT projects are, but you probably already knew that. We covered how the graph of their outcomes is not a bell curve, although that’s almost everyone’s assumption for everything. On the contrary, it’s much worse: the “tail” of budget overruns is long and fat.

The subject of Part I was “Why Big Software Projects Become Disasters” but in fact, most of the lessons we get from non-computer projects apply here as well. They are human problems and are not specific to computers at all. In fact, computer projects are worse! As Flyvbjerg says:

The global consultancy McKinsey got in touch with me and proposed that we do joint research. Its researchers had started investigating major information technology projects—the biggest of which cost more than $10 billion—and their preliminary numbers were so dismal that they said it would take a big improvement for IT projects to rise to the level of awfulness of transportation projects.

There are structural reasons for that, but in this article we’ll look at the psychological and political reasons this nightmare keeps happening. As the title says: it’s been well-studied and is mostly human nature and political reality. Some of the reasons are actually good (a bias towards optimism, thinking you’re unique), while some are downright evil (strategic misrepresentation). Overcoming them is a hard slog. But not impossible.

There are some big projects that have finished on time and on budget. In Part III, we’ll cover how that happens.

Bent Flyvbjerg has the world’s largest database of very large projects and how they turned out. He’s thought long and hard about what makes them work, and what makes them epic disasters. I’m drawing heavily from his work here, especially his book How Big Things Get Done, his scholarly article Top Ten Behavioral Biases in Project Management. and Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow.

Optimism Bias

This is the big one. Who likes a pessimist? What CEO gives a speech on the coming year and says, “We’re probably going to do very poorly and lose out to our competitors”? What English Premier League manager tells his players at the start of the season, “No matter what you all do, we’ll probably get relegated”?

Optimism Bias crosses over into overconfidence bias, or hubris. That has its own section below. Note that I’m not using the term Dunning-Kruger; why do we need a trendy Pop Psychology term for something the ancient Greeks knew about?

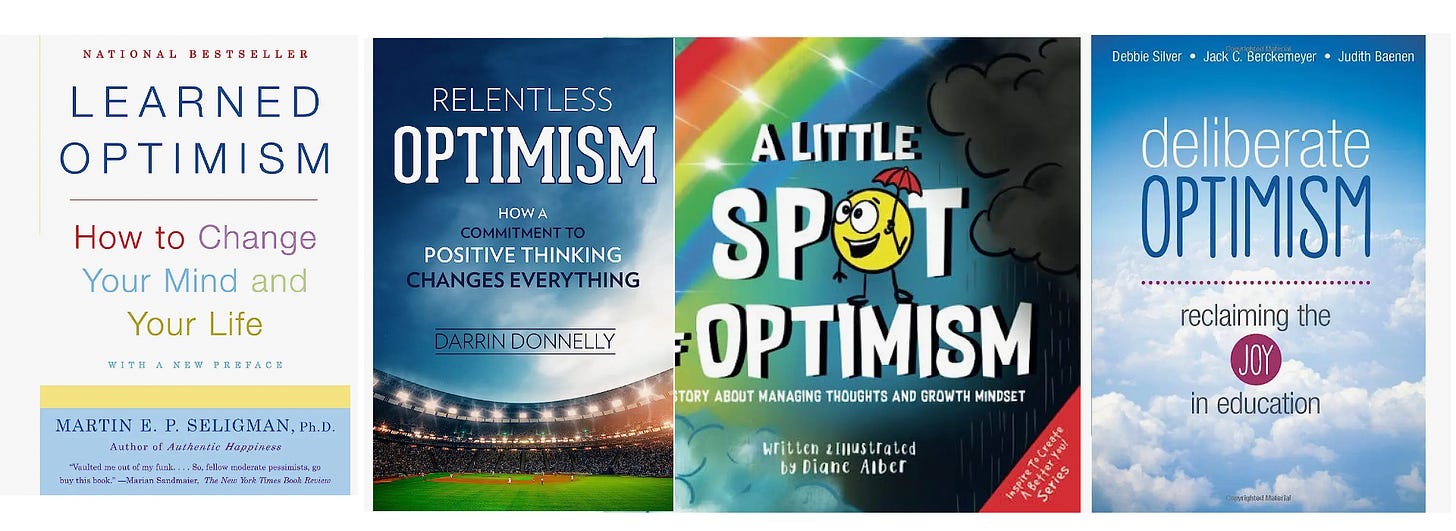

It’s also a very hard thing to get past. It’s everywhere: in ourselves, and in our estimations of other people. It’s a popular word to include in your book title:

There’s a TV series whose very name celebrates it:

One can even argue that it’s good to be optimistic, and optimists tend to rise to the top of whatever group they’re in. As Kahneman shows, it’s good for your mental health:

An optimistic attitude is largely inherited, and it is part of a general disposition for well-being, which may also include a preference for seeing the bright side of everything. If you were allowed one wish for your child, seriously consider wishing him or her optimism. Optimists are normally cheerful and happy, and therefore popular; they are resilient in adapting to failures and hardships, their chances of clinical depression are reduced, their immune system is stronger, they take better care of their health, they feel healthier than others and are in fact likely to live longer. A study of people who exaggerate their expected life span beyond actuarial predictions showed that they work longer hours, are more optimistic about their future income, are more likely to remarry after divorce (the classic "triumph of hope over experience"), and are more prone to bet on individual stocks. Of course, the blessings of optimism are offered only to individuals who are only mildly biased and who are able to "accentuate the positive" without losing track of reality.

“Optimism Bias” is a very well-studied topic in the scholarly literature, e.g. here

The optimism bias is defined as the difference between a person’s expectation and the outcome that follows. If expectations are better than reality, the bias is optimistic; if reality is better than expected, the bias is pessimistic. The extent of the optimism bias is thus measured empirically by recording an individual’s expectations before an event unfolds and contrasting those with the outcomes that transpire.

and this article on students’ expectations of future income and ease of repaying debt. You can find many more, e.g. a majority of drivers rate their driving skills as above average (the Lake Wobegon Effect).

It’s Good for Society

Even worse for our chances of dealing with Optimism Bias, it is actually a positive force for society. What entrepreneur would sink his life savings into a business, convince other people to invest in it and work for it, and work 18-hour days for years on end, if he or she wasn’t optimistic? We need the optimists to keep the economy humming.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in Antifragile, explains that optimism and even irrational over-optimism is good overall, although maybe not so good for you if your restaurant fails:

We saw that the restaurant business is wonderfully efficient precisely because restaurants, being vulnerable, go bankrupt every minute, and entrepreneurs ignore such a possibility, as they think that they will beat the odds. In other words, some class of rash, even suicidal, risk taking is healthy for the economy — under the condition that not all people take the same risks and that these risks remain small and localized.

Hubris, or Over-Confidence

This is topical right now with the Titan submersible. The founder, Stockton Rush, is descended from two signers of the Declaration of Independence. He had hubris, for sure. He said, about his submersible:

I’d like to be remembered as an innovator. I think it was General MacArthur said, you’re remembered for the rules you break, and you know I've broken some rules to make this. I think I've broken them with logic and good engineering behind me. The carbon fiber and titanium: there's a rule you don't do that. Well I did.

[Note: According to Wikipedia, MacArthur is remembered for his accomplishments and failures, the Occupation of Japan, “I shall return,” and being fired by Truman, not the rules he broke.}

We like our leaders to be confident. Stockton Rush talked people into spending $250,000 to ride on his sub, after all, risking that what actually happened would happen.

He said in an email,

I have grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation and new entrants from entering their small existing market. Since Guillermo and I started OceanGate, we have heard the baseless cries of "you are going to kill someone" way too often. I take this as a serious personal insult.

Frequently you see this attitude among the hubristic: I call it “meta-business instead of business.” They focus on the plot of their personal movie instead of the business itself. It’s Hollywood Scriptwriting 101: the hero dares, danger threatens, he triumphs, the end; roll credits.

There’s no better example of meta-business than Elizabeth Holmes’ rhetoric, pre-conviction and pre-prison sentence:

this is what happens when you work to change things: first they think you're crazy, then they fight you, and then all of a sudden you change the world.

Note that the reality of making a blood-testing device wasn’t the star in her drama: the plot summary was it.

If you’re a soldier in combat and your officer orders your squad to take that building, you don’t want to hear, “I don’t think this will work, but go try it anyway.” If you’re a financial expert trying to get invited on CNBC to prognosticate, you need to appear totally confident about your predictions.

And speaking of financial “expertise,” Kahneman tells us:

For a number of years, professors at Duke University conducted a survey in which the chief financial officers of large corporations estimated the returns of the Standard & Poor's index over the following year. The Duke scholars collected 11,600 such forecasts and examined their accuracy. The conclusion was straightforward: financial officers of large corporations had no clue about the short-term future of the stock market; the correlation between their estimates and the true value was slightly less than zero!

In other words, a monkey throwing darts would have a better success rate than these titans of industry.

We can’t expect that a leader of a very large organization have no hubris or to be cowed by the risks. All we can do is be aware of it and apply the proper discounts.

Strategic Misrepresentation

If we look at very large projects, political factors come to the fore. When you have to get the taxpayers to finance you, it’s not just your own optimism. Let’s look at two of the biggest projects: hosting the Olympics, and the California Bullet Train.

Olympic Games

The Olympics were held in Montreal in 1976. The Mayor, Jean Drapeau, said about the prospects of completing the project within its budget,

The Montreal Olympics can no more have a deficit than a man can have a baby.

The 1976 Olympics went 720% over budget. It took 30 years for the citizens to pay off the debt. Yet Drapeau was not even voted out of office! So there really isn’t any penalty for strategically lying, and let’s call it what it is. As Flyvbjerg and Alison Stewart said here in a study of Olympics cities:

We discovered that the Games stand out in two distinct ways compared to other megaprojects: (1) The Games overrun with 100 per cent consistency. No other type of megaproject is this consistent regarding cost overrun. Other project types are typically on budget from time to time, but not the Olympics. (2) With an average cost overrun in real terms of 179 per cent – and 324 per cent in nominal terms – overruns in the Games have historically been significantly larger than for other types of megaprojects, including infrastructure, construction, ICT, and dams

If your city is accepted as an Olympics host, you’ve just signed a blank check. Any cost overruns, whether they’re your fault or not, are on you.

California Bullet Train

In 2008 (yes, 17 years ago), California voters approved a bond measure, issuing $9.95 billion in general obligation bonds, including $9 billion for the planning and construction of an 800-mile high-speed rail system connecting San Francisco to Los Angeles (Ballotpedia). Proposition 1A said the high-speed train would need to move at a speed of at least 200 mph and connect San Francisco to Los Angeles in 2 ⅔ hours.

Let’s stop for a minute: these are aspirations, not a plan. People were asked to decide if they liked the idea of a European or Japanese-style bullet train. There was not even a route picked out, let alone a detailed plan.

According to the LA Times 14 years later, the initial estimate was $33 billion.

The 2022 business plan estimates that the full, 500-mile high-speed system between Los Angeles and San Francisco will cost as much as $105 billion, up from $100 billion two years ago.

Now, Forbes tells us that the money has finally been released to build the first, 171-mile stretch of track, neither end of which is close to Los Angeles or San Francisco. According to Wikipedia, operation will begin around 2030.

But wait: it gets worse. According to this 2025 story, the new director of the project, Ian Choudri, thinks it will take two more decades to finish the initial segment. Read that sentence again.

How Fast, Again?

Remember that promise of a 200 mph train that sold the project, not to mention the very word “bullet?”

Only electric and maglev trains go that fast. Yet there is still some question whether the first Merced-Bakersfield link will even be electrified! If it isn’t, then it will use diesel locomotives. There won’t be many climate change benefits to that, if any.

It turns out that no one wants to tell you how fast that will be, but this Wikipedia article implies that even 90 mph is probably optimistic. Doing some rough math, the LA to SF time can’t be less than four hours, and given that you’ll go through the San Joaquin Valley, maybe much more.

Amtrak shows that a train journey now from San Francisco to Los Angeles takes 10 hours and costs about $60.

The Governor is not happy about that:

Newsom’s administration wants electrification.

“We believe the time for slow, diesel-emitting rail is over, and we remain committed to a transportation future that moves people quickly and does so without further polluting our environment,” spokesman Daniel Lopez said in a statement.

Yes, It IS a Deliberate Lie

“Strategic misrepresentation” sounds dishonest, and it is: it means lowballing the estimate in order to get the project approved. If you’re suspecting that politicians and other lowlifes do that, you’re correct, and they’ve even admitted it! Flyvbjerg says,

The French architect Jean Nouvel, a winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, architecture's Nobel, was blunt about the purpose of most cost estimates for signature architecture. "In France, there is often a theoretical budget that is given because it is the sum that politically has been released to do something. In three out of four cases this sum does not correspond to anything in technical terms. This is a budget that was made because it could be accepted politically. The real price comes later. The politicians make the real price public where they want and when they want."

In other words, the estimate is just what they think the public will accept, not anything real.

Shocking? Willie Brown, who was mayor of San Francisco and Speaker of the California Assembly, said in 2013 when he was safely out of office:

News that the Transbay Terminal is something like $300 million over budget should not come as a shock to anyone.

We always knew the initial estimate was way under the real cost. Just like we never had a real cost for the Central Subway or the Bay Bridge or any other massive construction project. So get off it.

In the world of civic projects, the first budget is really just a down payment. If people knew the real cost from the start, nothing would ever be approved.

The idea is to get going. Start digging a hole and make it so big, there's no alternative to coming up with the money to fill it in.

Former Mayor Brown just called you a sucker if you believed the initial estimate.

In home renovation, “start digging a hole” translates into the well-known stereotype of bad contractors: “knock down a wall, then disappear for two months.”

Why Does That Strategy Work?

Since it’s so prevalent, it must work. Indeed, no one would ever be elected Governor of California if they promised to just write off the money spent as a mistake and walk away. As with the 2008 ballot initiative: if you’re for the Bullet Train, it’s a moral commitment and no amount of money or delay is too much. It’s like asking “how much is your child’s life worth?”

At any rate, the social scientists call this “escalation of commitment.” The more you spend on something, the more you’re committed to it. Flyvbjerg says in the Footnotes:

Escalation of commitment applies to individuals, groups, and whole organizations. It was first described by Barry M. Staw in 1976 with later work by Joel Brockner, Barry Staw, Dustin J. Sleesman et al., and Helga Drummond. Economists use related terms like sunk-cost fallacy (Arkes and Blumer, 1985) and lock-in (Cantarelli et al., 2010) to describe similar phenomena. Escalation of commitment is captured in popular expressions such as "Throwing good money after bad" and "In for a penny, in for a pound." In its original definition, escalation of commitment is unreflected and nondeliberate. As with other cognitive biases, people don't know that they are subject to the bias.

We’ve all felt it: “I spent so much on this renovation project!” I can’t give up on it now!” It’s human.

But What If You Do Walk Away?

With the Olympics and the Bullet Train, there’s a sick feeling of inevitability. It’s unthinkable to just cancel it. But it’s thinkable, actually! The way to think of the choice is not,

“We spent $100 billion already, so we can’t waste that! With only $100 billion more, we’ll have ourselves a train!”

What you’ve already spent is gone. You can’t get it back. It’s called “sunk cost” and it’s irrelevant. You should think of it like this:

“Right now, today, would I spend $100 billion for a train?”

In Mexico City, former President Enrique Pena Nieto started a new airport project on Texcoco Lake, northeast of the city. At the time, it seemed like Mexico City’s airports were strained to the breaking point. A contract was awarded and the estimated cost was US$13.3 billion. At about 30% of the way into the project, a Presidential election was held, and Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), who had campaigned against the airport, won. He held a referendum on it, and about 70% of the vote went against it.

So he did the unthinkable and canceled it. I’m not a supporter of AMLO in general, but I have to admire his courage in keeping his promise and not throwing good money after bad. There is a cancellation cost to doing something like this when you have bonds issued, and the question of whether it does permanent damage to Mexico’s credibility depends on what else he does. Nonetheless, he did it.

Nature is healing that site.

“A Bias for Action”

We’ve all had the urge when starting a big project: we just want to get going! People will criticize a big IT project by saying “they haven’t written a single line of code yet!” Or a building project: “They haven’t turned a shovel full of dirt yet!” As if that’s a bad thing. I’d be more impressed if someone said, “We know every single expense down to the dollar and the man-hours required.”

Politicians and executives love to pose for photographs like this. They’re doing things! They’re taking action!

Here’s another:

Taking action is sexy. How many best selling books tout “A Passion for Thinking”? If you’re a business book author, “action” is a great word for your title. Everyone wants to think of himself or herself as a person of Action! Here are some books we find on Amazon when we search for “bias for action”:

Aside from regular human impatience, there are other, less innocent reasons why projects get underway before they should. One of them is the Willie Brown quote I mentioned: get started, make a big hole in the ground, and then they have to find the money to fill it up. Or the contractor’s practice of knocking down a wall for your renovation first.

Part III of this series will be about how to overcome the bias for action. If you’re an executive: those recommendations will not be as much fun as getting photographed at a ground-breaking ceremony.

Uniqueness Bias

Margaret Mead is credited with saying, "Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else" (although Quote Investigator denies that it was her).

Mister Rogers has a whole song, “You Are Special”

In nearly every project I’ve ever been on, the leader and everyone else felt that no one in the entire history of the world had ever done anything like this, and therefore there was nothing we could learn from anyone else.

I feel like a spoilsport when I say, “You are not special” in your project! But you’re not. When we step back and look at the history of similar projects, we find a range of outcomes and especially, bad events that have happened which we would not be expecting in ours.

“Man landing on the Moon” is the canonical example of “If we can do that, we can do anything.” In the 1960’s, obviously no one had ever gone to the Moon before. But NASA administration defeated the uniqueness bias. As Flyvbjerg says:

The NASA administration, mentioned above, balked when people insisted the Apollo program, with its aim of landing the first humans on the moon, was unique. How could it not be, as putting people on the moon had never been done before, people argued. The administration would have none of it. They deplored those who saw the program "as so special, as so exceptional," because such people did not understand the reality of the project. The administration insisted, in contrast, that "the basic knowledge and technology and the human and material resources necessary for the job already existed," so there was no reason to reinvent the wheel (Webb, 1969, p. 11, p. 61). The NASA-Apollo view of uniqueness bias saw this bias for what it is: a fallacy.

It’s only when we realize that we’re not special, and other people have done things that we can learn from, that we have any chance to escape the Montreal Olympics - California Bullet Train hell. Next post.

If one's own money were on the line, how often would this happen? The overall system appears to be set up to protect managers from failure, accountability, and liability, usually at the taxpayers' or investor's expense. There's been a lot of "drunken" behavior around projects and money since the 80s, which has only gotten worse as various legislative acts have shielded companies (and the government entities that regulate them) from any liability for harm or defect of their products and services. On top of that is senior managers getting huge bonuses even when they fail spectacularly, because boards are rubber stampers for whatever management wants. But there is one other psychological factor I'd add to your compelling list, and that's the hero leadership nonsense peddled in business schools since the 80s that has produced a generation of managers who go for bold "glory" projects that will make their names as "leaders." Everyone wants to be a Jack Welch or Steve Jobs or [name your favorite famous leader here], no matter the cost or collateral damage.

This is a great article and really nails it.

I too have been on many projects where what you describe were major issue including a near billion dollar software project in 1990 dollars, that two major companies got roped into funding, which ultimately was scraped! That project always had a schedule of being “just” 2 years from shipping for 6+ years, just enough to always keep the parents paying. It had other internal management issues as well that go beyond what was described here that reinforced the problems you described.

I’ve also worked on very large projects, not quite as large, that succeeded because they were not managed and sold in this way and honestly and appropriate pessimism(reservations/issues) was valued.