Previously I wrote about two other heroes of mine: Roger Ebert and Christopher Hitchens. Next time is Nessim Nicholas Taleb.

Who’s That?

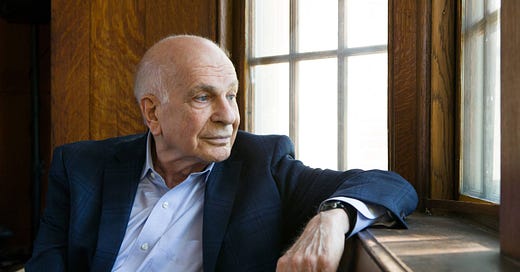

Daniel Kahneman (1934-2024) won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, despite being a psychologist and not an economist. If you ever took Economics and wondered if people actually behaved like the rational agents you read about: he and Amos Tversky, his partner, proved that they often don’t. He wrote the best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow, which you should read if you haven’t already.

I was at this talk.

Influence

Daniel Kahneman’s work has been cited more than 500,000 times, according to his Google Scholar profile. (By way of humility, my paper on software obviousness has been cited once!)

A hugely influential 1974 paper, Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (with Amos Tversky, his long-time collaborator) has been cited 53,477 times.

Intellectual Development

Daniel Kahneman was born in 1934 in Tel Aviv in British Mandatory Palestine, but grew up in Paris. He was there when the Nazis conquered France, but miraculously he escaped the Holocaust, and so did his family. Like all the Jews, the were forced to wear the yellow star marking them for deportation to the camps. His father was taken away, but then released when his employer intervened. They moved to Vichy France, which was not directly occupied, but eventually most Jews there perished as well. He has a story about an encounter with an SS soldier, which you can read in his Nobel essay, the upshot being that people don’t always behave the way you think they will.

The complexities of life in wartime France may have inspired his lifelong curiosity about human beings: why do they do what they do? “Psychology” was calling.

As he says in that Nobel essay,

But I was discovering that I was more interested in what made people believe in God than I was in whether God existed, and I was more curious about the origins of people’s peculiar convictions about right and wrong than I was about ethics.

A true psychologist. He’d found the questions he’d explore throughout his life: what do people really do, what thoughts lead them to do it, and in particular, why do they so often get things wrong? What cognitive illusions are they under that produce the bad results?

Kahneman moved to Israel just before it declared independence, and went to college there. He got his degree in psychology with a minor in mathematics, and those two subjects proved critical to his subsequent work. We’ll talk about that more shortly.

His Time in the IDF

Like everyone in Israel, he did his military duty. He spent a year as a platoon leader, and then was transferred to the Psychology unit. One of his duties was to assess candidates for officer training, and this proved a seminal event in his career. He describes it in detail in his Nobel essay. If you’ve ever had to interview a candidate for a job and decide if they’d succeed in it, you can relate to this. But in the Israeli case, lives are at stake: a bad officer can get his soldiers killed.

They were using a method that had been adapted from the British Army, involving a team exercise with a telephone pole and a wall.

For a good time, go to ChatGPT and ask it to explain this test. It actually does understand it and can tell you some team strategies that will work.

The Psychology team would observe the candidates, and they felt sure they could judge their leadership qualities.

We were looking for manifestations of the candidates’ characters, and we saw plenty: true leaders, loyal followers, empty boasters, wimps – there were all kinds. Under the stress of the event, we felt, the soldiers’ true nature would reveal itself, and we would be able to tell who would be a good leader and who would not. But the trouble was that, in fact, we could not tell.

How often do you make confident predictions but then never go back and see how well you did? The Israelis did; they looked at candidates’ subsequent performance in officer school, and got schooled in humility:

The story was always the same: our ability to predict performance at the school was negligible.

Most people would give up at that point. They’d schedule more interviewers, or maybe call the candidates’ teachers and friends. Not Kahneman. He realized they were assuming that the behavior they’d observed in the test would hold in the future. That’s just one sample! You can’t extrapolate from that to the general case.

This is a key statistical insight that he and Tversky expanded on in their influential paper Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases almost 20 years later. They call that particular fallacy “judgment by representativeness,” and you’re encouraged to read at least the first two pages of that. It’s beautifully written and a pleasure to read.

He visited various units of the army and observed the personality traits of the successful people there. Then he figured out how to interview for those traits:

I developed a structured interview schedule with a set of questions about various aspects of civilian life, which the interviewers were to use to generate ratings about six different aspects of personality (including, I remember, such things as “masculine pride” and “sense of obligation”).

This worked. The system stayed in use for decades.

I might note that this same failed tactic is still used today in many programming interviews: ask the candidate to solve a problem or write some code on the whiteboard..

You can observe a lot by just watching

Yogi Berra said that.

Kahneman’s Nobel biography, which is long but I’ll recommend it again, details numerous examples of him observing what everyone sees, but finding the lessons they all missed. Here are a few examples:

Austen Riggs

This was a major intellectual center for psychoanalysis. Each patient would be discussed at a Friday meeting. At one meeting, the patient had committed suicide the night before.

On one of those Fridays, the meeting took place and was conducted as usual, despite the fact that the patient had committed suicide during the night. It was a remarkably honest and open discussion, marked by the contradiction between the powerful retrospective sense of the inevitability of the event and the obvious fact that the event had not been foreseen.

Hindsight bias! Everyone “knew” this would happen, despite the fact that no one said so earlier. Likewise, everyone knows that the Union had to win the Civil War, and the Nazis had to lose World War Two. What would they have said in 1862 or 1940?

The psychology of single questions, and sample size

Many psychological traits require long descriptions in the DSM, and take many tests and interviews to measure. Being a scientist, Kahneman looked for a simpler and statistically valid way.

My model for this kind of psychology was research reported by Walter Mischel (1961a, 1961b) in which he devised two questions that he posed to samples of children in Caribbean islands: “You can have this (small) lollipop today, or this (large) lollipop tomorrow,” and “Now let’s pretend that there is a magic man … who could change you into anything that you would want to be, what you would want to be?”

These tests turned out to be remarkably correlated with other characteristics of the child. Yet he didn’t publish them, because they didn’t replicate as well as he’d hoped. As someone trained in statistics, he realized the importance of sample size.

I realized only gradually that my aspirations demanded more statistical power and therefore much larger samples than I was intuitively inclined to run. This observation also came in handy some time later.

Regression to the mean

I had the most satisfying Eureka experience of my career while attempting to teach flight instructors that praise is more effective than punishment for promoting skill-learning.

He goes on to explain that since, after an exceptional performance, a subsequent try will probably be closer to the mean, rewarding a good try can look like it doesn’t work, because the next try will probably be worse. Similarly, punishing a bad performance looks like it works, since the next try will tend to be better.

You can see the same effect at a 4-day golf tournament: the leader on Thursday rarely ends up winning the tournament. His score on Thursday is an anomaly and he reverts to his norm on the next three days.

Collaborating with Amos Tversky

If you want to read another Lennon & McCartney or Rodgers & Hart story of two people adding up to more than their sum, read this section. He’s describing something like love.

The experience was magical. I had enjoyed collaborative work before, but this was something different. Amos was often described by people who knew him as the smartest person they knew. He was also very funny, with an endless supply of jokes appropriate to every nuance of a situation. In his presence, I became funny as well, and the result was that we could spend hours of solid work in continuous mirth. … I have probably shared more than half of the laughs of my life with Amos.

…..

Amos and I shared the wonder of together owning a goose that could lay golden eggs – a joint mind that was better than our separate minds. The statistical record confirms that our joint work was superior, or at least more influential, than the work we did individually.

Bayesian Thinking

If you want to understand the jargon of Silicon Valley bros, learn what “your priors” means. They say that all the time. Wikipedia explains it. Your “prior” is your going-in (or prior) assumption about reality; for example, if you know that a population is 70% lawyers and 30% engineers, then that determines your prior guess for a person drawn from that population (most likely a lawyer). Bayesian probability involves adjusting your estimate based on new information as it comes in.

One manager in statistics whom I knew at Google had an interview question she always asked candidates: “Are you a frequentist or a Bayesian? Explain.” Unfortunately, when most of us learn about probability in college, the frequentist point of view is over-represented. We learn about coin tosses, dice and card games, or urns full of red and blue balls, where an exact probability can be asserted. There is a whole field of study based on those frequentist assumptions.

Most of reality is not like that. People ask, “what is the probability that an earthquake will occur this year?” In fact, there is no number that one can prove about that event! The 2008 financial crisis was a textbook case of defining certain events as “unlikely” because they’d never happened before. They may have been unlikely, but they were still possible. My next intellectual hero, Nessim Nicholas Taleb, has his own bestselling book, The Black Swan, on that topic. A Black Swan event is something that “should” never happen, but sometimes it does anyway.

Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, a hugely influential paper from Kahneman & Tversky, only mentions the word “Bayes” twice, but it’s all about Bayesian probability and how humans don’t understand it. Those illusions they enumerate (representativeness, prior probability, sample size, predictability, validity, regression to the mean, availability) are the basis of much of their subsequent work. When they applied these insights to human behavior with money, they hit the jackpot: we don’t behave like the rational, profit-maximizing agents in economics textbooks; instead, we suffer from those illusions and many more. The entire field of Behavioral Economics is unimaginable without them.

Thinking Fast and Slow

I think this is Kahneman’s master work, and it was a bestselling book. Here are some of the things you’ll learn from it:

How Your Brain Works

The book begins with a description of fast-reacting thinking and the slower, rational type, which Kahneman calls System 1 and System 2. System 1 is our immediate reaction to things, while System 2 is the more deliberate thinking that we imagine is “us.” A large part of the book is categorizing the errors that System 1 is prone to.

Sample Size

How often do you see news stories like this?

In a telephone poll of 300 seniors, 60% support the President.

If it said, “a poll of 30 voters” or “a poll of 3 million voters” you might react differently, but 300 vs. 3000? How would you evaluate the likelihood that one is more prone to sampling error? Of course, there are formulas that tell you that, but even many academics don’t use them.

This one reminds me of another Yogi Berra quote: “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice, but in practice there is”

Amos and I called our first joint article "Belief in the Law of Small Numbers." We explained, tongue-in-cheek, that "intuitions about random sampling appear to satisfy the law of small numbers, which asserts that the law of large numbers applies to small numbers as well." We also included a strongly worded recommendation that researchers regard their "statistical intuitions with proper suspicion and replace impression formation by computation whenever possible."

Anchoring

Merely seeing one number influences your guess of another one, even though your System 2 knows there’s no relationship.

Amos and I once rigged a wheel of fortune. It was marked from 0 to 100, but we had it built so that it would stop only at 10 or 65. We recruited students of the University of Oregon as participants in our experiment. One of us would stand in front of a small group, spin the wheel, and ask them to write down the number on which the wheel stopped, which of course was either 10 or 65. We then asked them two questions:

Is the percentage of African nations among UN members larger or smaller than the number you just wrote?

What is your best guess of the percentage of African nations in the UN?

Merely writing down the 10 or the 65 made them guess 25% and 45%, respectively. Hard to believe, but it’s true. The anchoring bias is explained in considerable detail in that chapter.

Should You Trust That Expert?

Millions read Malcolm Gladwell’s bestselling book Blink, about the value of intuition. It opens with the story of a supposedly authentic Greek statue and a group of art experts charged with deciding if it really was authentic. Several experts had a strong visceral reaction that it was fake, but they couldn’t explain why they “knew” that. Many readers came away with the view that you should always trust your intuition (something Gladwell himself doesn’t believe).

There is an entire chapter about the intuitions of professionals. Kahneman collaborated with another psychologist who vehemently disagreed with him, purely to see if they could bridge their differences. They ended up agreeing more than they expected about how one ought to decide whether to trust an “expert.”

"How much expertise does she have in this particular task? How much practice has she had?"

"She is very confident in her decision, but subjective confidence is a poor index of the accuracy of a judgment."

"Did he really have an opportunity to learn? How quick and how clear was the feedback he received on his judgments?"

There are many brilliant chapters in this book, but I include this one because it relates to a question I actually got to ask Dr. Kahneman when he came to Google (below).

And Much More

There are many more major insights that you’ll get from this book. Read it.

Are People Listening?

In Kahneman’s visit, I was part of the team helping out, and thus I got to attend a lunch with him and a small group. I asked him, “Dr. Kahneman, you’ve been writing about thinking for over 40 years. Do you think you’ve changed people’s thinking?”

He smiled and said, “No, not even my own.” He proceeded to relate how he and his daughter were in the hospital when his wife was being treated. An attractive young doctor spoke to them articulately about the disease his wife was being treated for.

In the elevator with his daughter, he said, “She speaks very well!” His daughter had learned his work better than he had, and reminded him that the important thing was whether the doctor had experience with this disease.

He was being too modest, I think. His influence is everywhere. I feel lucky to have met him.