I just finished rereading Middlemarch. I also watched the BBC series (which may be free on Kanopy for you). So here’s a review. This does contain plot spoilers.

Unlike literary book reviews one often sees, I’m not showing off my literary erudition here. Rather it’s more like a movie trailer, showing you why you’d like it.

Read it. Middlemarch was published in 1872, at the very height of Queen Victoria’s reign in England. George Eliot was the pseudonym adopted by Mary Ann Evans

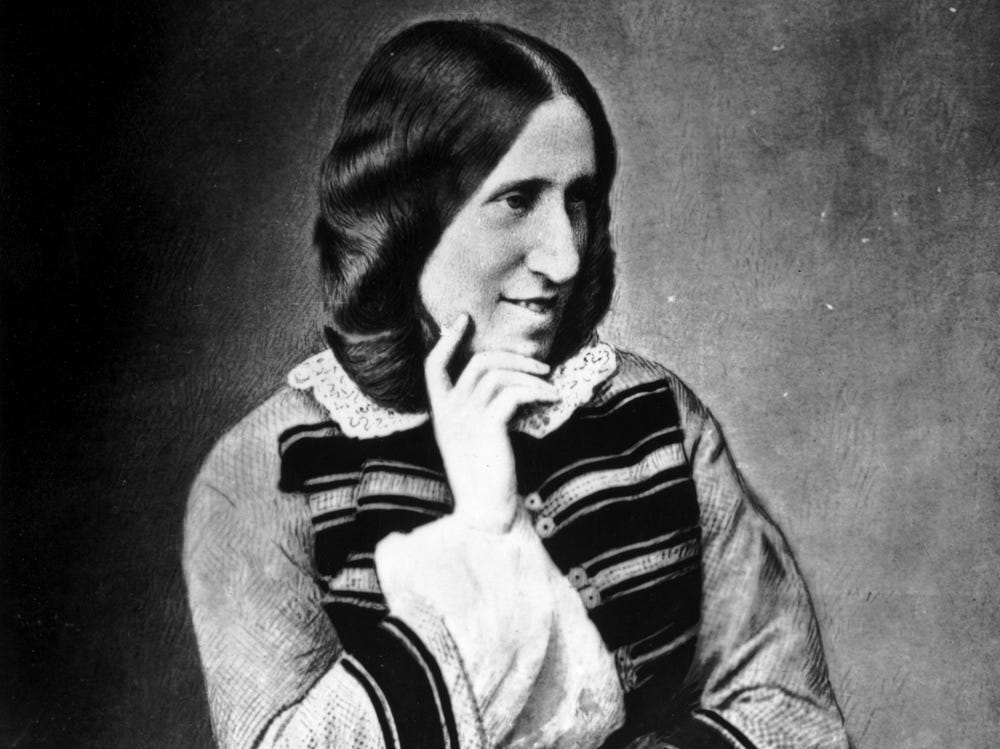

and I won’t go into why she chose a male pen name. I do note that that portrait doesn’t seem nearly as ugly as Henry James’ extravagantly florid description:

To begin with she is magnificently ugly — deliciously hideous. She has a low forehead, a dull grey eye, a vast pendulous nose, a huge mouth, full of uneven teeth & a chin & jawbone qui n'en finissent pas ["which never end"] ... Now in this vast ugliness resides a most powerful beauty which, in a very few minutes steals forth & charms the mind, so that you end as I ended, in falling in love with her.

That’s a portrait, though, so we can assume the painter did his best to make her look good. Here’s an actual photograph:

Things You Need to Know

Given that the book was written 150 years ago, and (unless you’re British) describes a much different society than yours, there are a few things that it’s helpful to know, although remarkably few. If you like Jane Austen’s novels, you’re way ahead of the game. This is not a historical essay; just some facts to know.

If you actually are British, please forgive the Americanisms. I’m sure I’ve gotten a lot of nuances wrong.

Clergy

The social position of the clergy was drastically different from what it is now in England. It was a financially secure job, ideal for a second son who could not inherit the family property (“primogeniture” meant that the estate was not divided among the sons; it all passed to the oldest).

The Church of England was the official church and most people attended services. There were, of course, other religions, which were tolerated but not quite as socially acceptable. In particular, the “dissenters” are mentioned in several places.

Clergy were expected to be well-educated, and this is a major plot point in the book. Fred Vincy has been expensively educated by his father with the expectation that he would become a vicar and rise in the world.

In Middlemarch, especially, a “living” for a vicar or Rector meant a house and a lot of agricultural land whose tenants financially supported him, either with tithes or taxes. Before technology took over, and the United States started exporting massive amounts of food, English agriculture was extremely profitable. Clergymen often had plenty of disposable income and time to pursue their own interests.

Politics

The story takes place in 1830 when the Reform Bill was being considered in Parliament. The French and American revolutions had made democracy and expansion of the electorate a critical issue, and discussions of “the Bill” appear in multiple places in the book (but giving women the vote was just not in the cards yet).

Mr. Brooke was a Whig, which was the reform party at the time. He’s an ineffectual figure of fun in the book, and he eventually runs for Parliament and is humiliated in his one and only public speech. He hires Ladislaw, a young man who’s another major figure in the book, as his editor for the newspaper he bought. In the BBC adaptation, at least, Ladislaw is a brilliant writer and public speaker, and we find out in the epilogue that he’s eventually elected to Parliament.

Despite all that, I think it’s a mistake to describe Middlemarch as a political book. Everything is seen through a political lens nowadays, but to me the politics is a backdrop more than the main plot. We have a mention of the railroad coming through, but it’s also a mistake to claim the book is about Middlemarch “coping with change.” It’s just the setting.

Money, Rank, and Marriage

This is the big one, beyond love, morality, class, and small-town gossip which are the main theme of the novel.

“Being of good blood” meant coming from a “good” family, meaning the nobility or at least a very respectable family with no hint of scandal. This was hugely important. Later on, in the early 20th century, there were lots of people with noble blood but no cash. They often married Americans, who had the cash and craved the prestige. Winston Churchill, for example, had an American mother.

Anyway, marriage was taken very seriously, as of course it was in Jane Austen’s books as well. Whom a girl should marry was something everyone in town had an opinion on, and yet we see in Middlemarch that love could sometimes be a determining factor. Many girls, of course dutifully marry a man their parents approve of. Others (like Dorothea) insist on doing what they want no matter what anyone says.

Everyone in Middlemarch knows how much income everyone else has, to the pence. “He has a thousand a year” would be an unexceptionable thing to say, and not at all bad manners. Marrying someone with no income (and no rank) is a life-destroying thing to do.

What It’s About (and Why to Read It)

Middlemarch is a brilliant picture of a small rural town and its interlocking family relationships. More than that, it’s a meditation on love, morality, money, ambition, and religion, and has a psychological insight into its characters that’s astonishing for its period. Some readers apparently find it difficult reading, and while I quite often put books down for being too much effort, I didn’t find Middlemarch difficult. Occasionally you see a sentence that makes you scratch your head, but usually you can just skip over it.

The reason to read Middlemarch, like almost any novel, is that you care about the characters. The plot arises from their needs and wants, rather than the characters being chosen to fit a particular “type” in the plot.

“How should a young person find their place in this world?” is the big question that it confronts, along with “How should we behave?” There are seven people all near 20: Fred, Dorothea, Celia, Ladislaw, Rosamund, Mary, and Lydgate (first name “Tertius,” which only his wife uses), and it’s their adventures that drive the story. Of course many older people help them, hinder them, gossip about them, and pursue their own agendas, too. That’s why it’s a long book!

Dorothea and Casaubon

Dorothea, who with her sister Celia lives with their uncle Mr. Brooke, is clearly the author’s main interest, since she opens and closes the book. She is an idealistic, religious person whose overriding interest is doing something worthwhile with her life and with her money. Celia is more practical-minded, and urges her to marry Sir James Chettam, who has a good fortune and is deeply interested in her.

Dorothea’s initial interest is in building better cottages for the workers on their estate, and Sir James supports her, in a transparent effort to win her favor. All for naught. She is drawn instead to the Rev. Edward Casaubon, a 45-year-old minister with all the personality of cold mashed potatoes, whose life work is “A Key to all Mythologies,” apparently a unifying theme for every mythology known to man. A daunting task, eh? She thinks he has “a great soul.”

This passage has Casaubon having dinner with Dorothea, Celia, and Mr. Brooke, and the conversation presages a good bit of the story to come. I put in bold the parts I want to talk about.

"Yes," said Mr. Brooke, with an easy smile, "but I have documents. I began a long while ago to collect documents. They want arranging, but when a question has struck me, I have written to somebody and got an answer. I have documents at my back. But now, how do you arrange your documents?"

"In pigeon-holes partly," said Mr. Casaubon, with rather a startled air of effort.

"Ah, pigeon-holes will not do. I have tried pigeon-holes, but everything gets mixed in pigeon-holes: I never know whether a paper is in A or Z."

"I wish you would let me sort your papers for you, uncle," said Dorothea. "I would letter them all, and then make a list of subjects under each letter."

Mr. Casaubon gravely smiled approval, and said to Mr. Brooke, "You have an excellent secretary at hand, you perceive."

"No, no," said Mr. Brooke, shaking his head; "I cannot let young ladies meddle with my documents. Young ladies are too flighty."

Dorothea felt hurt. Mr. Casaubon would think that her uncle had some special reason for delivering this opinion, whereas the remark lay in his mind as lightly as the broken wing of an insect among all the other fragments there, and a chance current had sent it alighting on her.

When the two girls were in the drawing-room alone, Celia said "How very ugly Mr. Casaubon is!"

"Celia! He is one of the most distinguished-looking men I ever saw. He is remarkably like the portrait of Locke. He has the same deep eye-sockets."

"Had Locke those two white moles with hairs on them?"

"Oh, I dare say! when people of a certain sort looked at him," said Dorothea, walking away a little.

"Mr. Casaubon is so sallow."

"All the better. I suppose you admire a man with the complexion of a cochon de lait."

"Dodo!" exclaimed Celia, looking after her in surprise. "I never heard you make such a comparison before."

"Why should I make it before the occasion came? It is a good comparison: the match is perfect."

Miss Brooke was clearly forgetting herself, and Celia thought so.

"I wonder you show temper, Dorothea."

"It is so painful in you, Celia, that you will look at human beings as if they were merely animals with a toilet, and never see the great soul in a man's face."

"Has Mr. Casaubon a great soul?" Celia was not without a touch of naive malice. "Yes, I believe he has," said Dorothea, with the full voice of decision. "Everything I see in him corresponds to his pamphlet on Biblical Cosmology."

"He talks very little," said Celia

"There is no one for him to talk to."

Celia thought privately, "Dorothea quite despises Sir James Chettam; I believe she would not accept him." Celia felt that this was a pity. She had never been deceived as to the object of the baronet's interest. Sometimes, indeed, she had reflected that Dodo would perhaps not make a husband happy who had not her way of looking at things, and stifled in the depths of her heart was the feeling that her sister was too religious for family comfort. Notions and scruples were like spilt needles, making one afraid of treading, or sitting down, or even eating.

The parts I put in bold are very characteristic of Middlemarch and some of the best things about it. Eliot quite often features a conversation where she tells us what everyone is thinking even if they don’t say it, and comments on it. “The remark lay in his mind as lightly as the broken wing of an insect among all the other fragments there” is a brilliant commentary on Mr. Brooke’s confused mind, which we’ll see throughout the book.

As you might guess, they do get married, and let’s just say it doesn’t turn out well.

Fred Vincy and Mary Garth

These are two of my favorite people in the book, along with Mary’s father Caleb. They are not of noble blood; they’re solidly middle-class. Caleb is an “agent” or farm manager. If you are of noble blood and have some land to manage, Caleb is the guy you hire to manage it for you.

Fred is the scapegrace son of Walter Vincy, a businessman and future mayor of Middlemarch. Walter wants him to be a clergyman, but Fred’s failed his exams and dropped out of university. He and Mary have loved each other since childhood, but whether and when they’ll get married is left open to the very end (spoiler: they do, as you knew they would). Fred doesn’t want to enter the clergy and Mary has said she won’t marry him if he does. However, she hasn’t said she will marry him if he doesn’t. He’s dying for her to say it, but she won’t.

He’s gotten into debt with gambling and other loose living. This exchange with Mary is an example of the things I love about this book (this is Mary speaking at first). As before, I put in bold some of the author’s comments.

"Oh, I am not angry, except with the ways of the world. I do like to be spoken to as if I had common-sense. I really often feel as if I could understand a little more than I ever hear even from young gentlemen who have been to college."

Mary had recovered, and she spoke with a suppressed rippling under-current of laughter pleasant to hear.

"I don't care how merry you are at my expense this morning," said Fred, "I thought you looked so sad when you came up-stairs. It is a shame you should stay here to be bullied in that way."

"Oh, I have an easy life—by comparison. I have tried being a teacher, and I am not fit for that: my mind is too fond of wandering on its own way. I think any hardship is better than pretending to do what one is paid for, and never really doing it. Everything here I can do as well as any one else could; perhaps better than some Rosy, for example. [Fred’s sister] Though she is just the sort of beautiful creature that is imprisoned with ogres in fairy tales."

"Rosy!" cried Fred, in a tone of profound brotherly scepticism.

"Come, Fred!" said Mary, emphatically; "you have no right to be so critical."

“Do you mean anything particular just now?"

"No, I mean something general always."

"Oh, that I am idle and extravagant. Well, I am not fit to be a poor man. I should not have made a bad fellow if I had been rich."

"You would have done your duty in that state of life to which it has not pleased God to call you," said Mary, laughing.

"Well, I couldn't do my duty as a clergyman, any more than you could do yours as a governess. You ought to have a little fellow-feeling there, Mary."

"I never said you ought to be a clergyman. There are other sorts of work. It seems to me very miserable not to resolve on some course and act accordingly."

“So I could, if—" Fred broke off, and stood up, leaning against the mantel-piece.

"If you were sure you should not have a fortune?"

"I did not say that. You want to quarrel with me. It is too bad of you to be guided by what other people say about me."

"How can I want to quarrel with you? I should be quarrelling with all my new books," said Mary, lifting the volume on the table.

"However naughty you may be to other people, you are good to me."

"Because I like you better than any one else. But I know you despise me."

"Yes, I do —a little," said Mary, nodding, with a smile.

"You would admire a stupendous fellow, who would have wise opinions about everything."

"Yes, I should." Mary was sewing swiftly, and seemed provokingly mistress of the situation.

When a conversation has taken a wrong turn for us, we only get farther and farther into the swamp of awkwardness. This was what Fred Vincy felt.

"I suppose a woman is never in love with any one she has always known—ever since she can remember; as a man often is. It is always some new fellow who strikes a girl."

"Let me see," said Mary, the corners of her mouth curling archly;

"I must go back on my experience. There is Juliet—she seems an example of what you say. But then Ophelia had probably known Hamlet a long while; and Brenda Troil—she had known Mordaunt Merton ever since they were children; but then he seems to have been an estimable young man; and Minna was still more deeply in love ….

All the younger folk eventually get married because hey, it’s a Victorian novel. I warned you there were plot spoilers here.

Eliot has immense sympathy for all classes of people, especially the Garths. Fred has spent time at Oxford so he’s seen how the well-born live, but he still loves Mary and Middlemarch. Caleb Garth, his father, is the sort of upright man that Jimmy Stewart would play in a Hollywood movie.

I could go on, but I should at least mention Lydgate and Bulstrode, since they lead to the climax.

Lydgate, Bulstrode, Raffles, and Rosamund

Money and debt are big plot-drivers in Middlemarch. Tertius Lydgate is a young doctor who’s studied in London and Paris, and is very interested in bringing modern scientific knowledge to town. He’s married Rosamund, who’s beautiful but accustomed to a life of luxury, and unwilling to live on the modest income that Lydgate earns.

An interesting historical note here is that the two doctors in town both earn most of their money other than by fees: by selling “prescriptions” to their patients. Knowing what we know now about pharmaceuticals, it’s hard to believe that most of these drugs (e.g. “black draughts”) actually did any good. Lydgate knows this and announces that he won’t sell any drugs, which doesn’t go over well in town. It also limits his income to fees, often from patients who pay very slowly.

Lydgate also gets into serious debt by living beyond his means, and the conflict with Rosamund over this drives much of the plot from here on out. That, and Bulstrode.

There’s an old saying that there are really only two plots in literature:

A man goes on a journey

A stranger comes to town

I think I would add a third:

3. Someone has a secret they really don’t want to get out

Middlemarch relies on #2. Lydgate and Bulstrode are both newcomers in Middlemarch, although Bulstrode has been there much longer. He arrived with a lot of money, and has become a banker. He’s also ostentatiously religious.

BUT: he has a dark secret about how he got his money (there’s your #3). Mr. Raffles is a swinish, drunken lout who knows all the secrets, and has been blackmailing Bulstrode about it. Long ago, Bulstrode gave him a lot of money to go to America and stay there. But now, oh no, he’s back! It’s Bulstrode’s worst nightmare. And no amount of money will induce Raffles to leave and never return.

Bulstrode has reluctantly put him up at his house. Here he is disdainfully asking Raffles how he came here.

"May I ask why you returned from America? I considered that the strong wish you expressed to go there, when an adequate sum was furnished, was tantamount to an engagement that you would remain there for life."

"Never knew that a wish to go to a place was the same thing as a wish to stay. But I did stay a matter of ten years; it didn't suit me to stay any longer. And I'm not going again, Nick." Here Mr. Raffles winked slowly as he looked at Mr. Bulstrode.

"Do you wish to be settled in any business? What is your calling now?"

"Thank you, my calling is to enjoy myself as much as I can. I don't care about working any more. If I did anything it would be a little travelling in the tobacco line or something of that sort, which takes a man into agreeable company. But not without an independence to fall back upon. That's what I want: I'm not so strong as I was, Nick, though I've got more color than you. I want an independence."

"That could be supplied to you, if you would engage to keep at a distance," said Mr. Bulstrode, perhaps with a little too much eagerness in his undertone.

"That must be as it suits my convenience," said Raffles coolly. "I see no reason why I shouldn't make a few acquaintances hereabout. I'm not ashamed of myself as company for anybody. I dropped my portmanteau at the turnpike when I got down change of linen genuine honor bright more than fronts and wristbands; and with this suit of mourning, straps and everything, I should do you credit among the nobs here." Mr. Raffles had pushed away his chair and looked down at himself, particularly at his straps. His chief intention was to annoy Bulstrode, but he really thought that his appearance now would produce a good effect, and that he was not only handsome and witty, but clad in a mourning style which implied solid connections.

"If you intend to rely on me in any way, Mr. Raffles," said Bulstrode, after a moment's pause, "you will expect to meet my wishes."

"Ah, to be sure," said Raffles, with a mocking cordiality. "Didn't I always do it? Lord, you made a pretty thing out of me, and I got but little. I've often thought since, I might have done better by telling the old woman that I'd found her daughter and her grandchild: it would have suited my feelings better; I've got a soft place in my heart. But you've buried the old lady by this time, I suppose—it's all one to her now. And you've got your fortune out of that profitable business which had such a blessing on it. You've taken to being a nob, buying land, being a country bashaw. Still in the Dissenting line, eh? Still godly? Or taken to the Church as more genteel?"

This time Mt Raffles' slow wink and slight protrusion of his tongue was worse than a nightmare, because it held the certitude that it was not a nightmare, but a waking misery. Mt Bulstrode felt a shuddering nausea, and did not speak, but was considering diligently whether he should not leave Raffles to do as he would, and simply defy him as a slanderer. The man would soon show himself disreputable enough to make people disbelieve him. "But not when he tells any ugly-looking truth about you," said discerning consciousness. And again: it seemed no wrong to keep Raffles at a distance, but Mr. Bulstrode shrank from the direct falsehood of denying true statements. It was one thing to look back on forgiven sins, nay, to explain questionable conformity to lax customs, and another to enter deliberately on the necessity of falsehood.

Conclusions

I’ve shown you some very long excerpts of key parts in the book, without giving away too much of the plot, so you should have a good idea of what you’re in for if you pick it up.

Note: I do this by screen-shots of the Kindle book, and then using a free online OCR tool. Usually the OCR is almost perfect.

It’s too bad there are no characters who’ve become as iconic as Elizabeth Bennett or Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice. For me, Middlemarch is a greater novel than any of Jane Austen’s books.