Anarchy in the US, Part 1

The Pullman Strike: You Are There

This is the first of a multi-part series.

Introduction

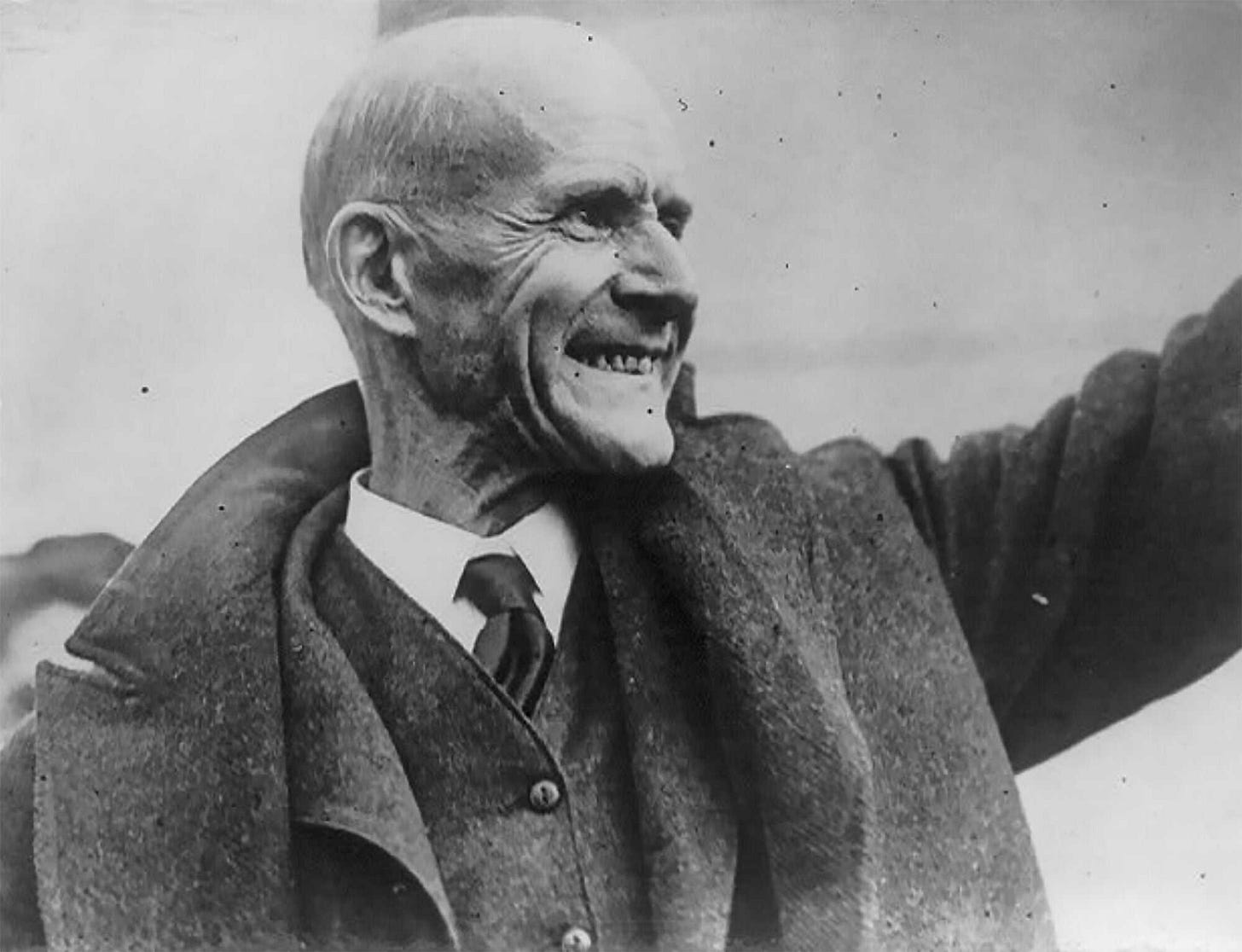

1894: the Pullman strike! Ken Burns has never done one of his trademark documentaries on it, and there are no iconic photographs like those of Lincoln, Grant, Frederick Douglass, or Robert E. Lee like we have for the Civil War. PBS’s The American Experience series did do a documentary on Eugene Debs, the leader of the union, but not on the strike itself. As a media event, it just doesn’t have legs.

This doesn’t pretend to be a complete or original history. You can find plenty of books about the Pullman strike, and there’s always Wikipedia. A big source for me was the excellent The Edge of Anarchy (Jack Kelly) .

I strive to avoid hindsight and look at what people actually thought and said back then, in the moment. So unlike most of the histories you’ll see, I try to practice the novelist’s dictum: “Show, don’t tell.” Most of these histories tell you, “The Chicago Tribune called him ‘Dictator Debs’. “ I’m showing it to you on page 1, July 1,1894:

Journalists often say they write “the first draft of history.” That usually gets thrown away later and condensed into a summary, but this is what they said in the moment.

NOTE: On newspapers.com you can see images of the newspapers back then, but you have to OCR them if you want them as text. This process is mostly accurate and I’ve tried to correct the errors, but I’m sure a few slipped through. Just let me know.

Personal note: Google Maps says it’s a 45 minute walk from my childhood home to the Florence Hotel, named after George Pullman’s daughter. I regularly went to the Pullman Library (still in business!) and had an account at the Pullman Bank. So I was curious. Especially since they never taught us anything about it in school, despite the Pullman neighborhood being so close.

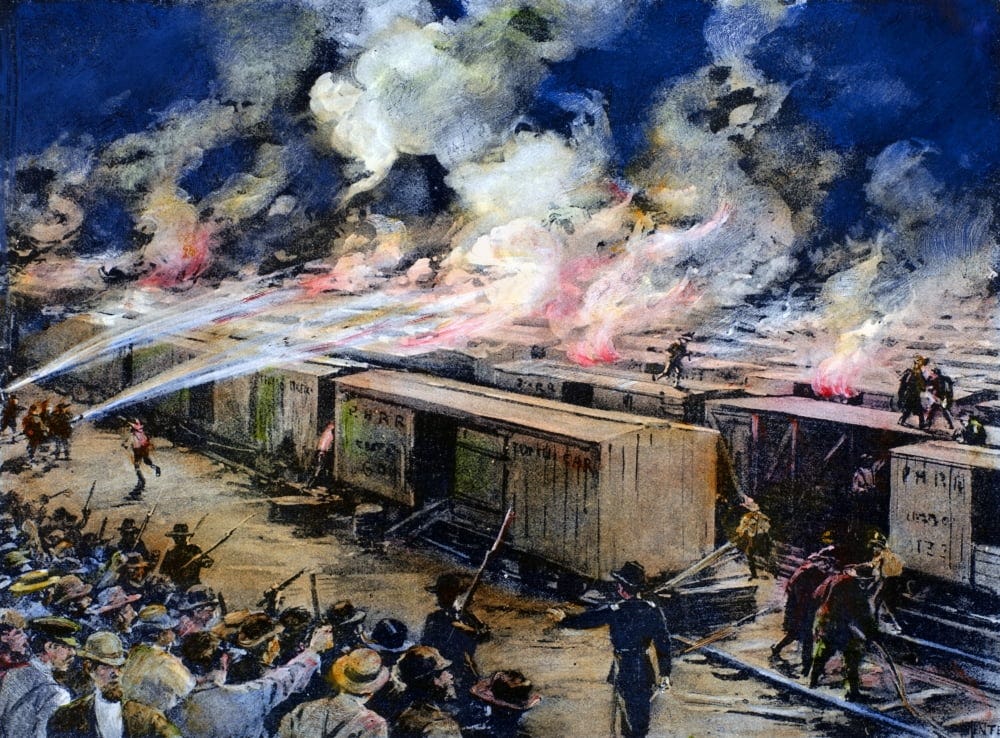

How often has the U.S. Army fired on civilians and killed them? How often did the President and Attorney General intervene personally against strikers? How often did citizens riot and set freight cars on fire? All those things happened.

This is a drawing. Photos are rather scarce for 1894.

If you think people hate “tech billionaires” now: they really hated railroad executives back then. The hatred exploded into riots with the strike. Railroad workers all over the country refused to service any train with Pullman cars, and the railroads refused to break their contracts with Pullman and eliminate them. The rail barons also wanted to maintain ranks against the American Railway Union. Eugene Debs tried to escalate even further and call a general strike of all labor, everywhere. That didn’t happen.

The Government’s Response

The US Attorney General, Richard Olney, said the country was on “the ragged edge of anarchy.” Imagine if the Internet went down for weeks: that’s what railroads meant in late 19th Century America. The Pullman strike disrupted the entire country, but in the end it was defeated completely, and its leader, Eugene Debs, went to jail.

George Pullman refused to even meet with the union, let alone accede to their demand for arbitration, despite the appeals of the Mayor of Chicago and the Governor of Illinois. Somehow he got away with it and the strike failed. Nowadays, we have the National Labor Relations Board, political leaders routinely step in, and unions are a fact of life. Back then, there was none of that. Arguably, the failed Pullman strike was a leading cause of the labor reforms in the 1930’s, although Eugene Debs died too soon to see them.

The Background

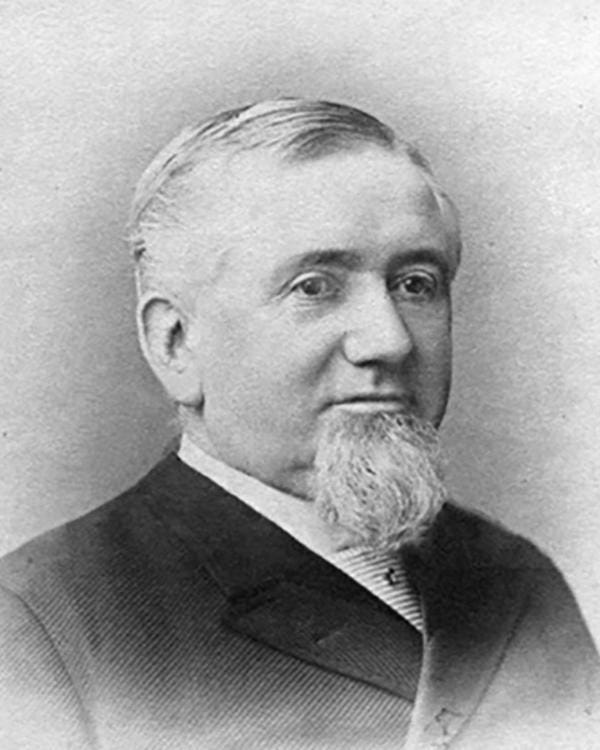

Before airplanes or cars, people and freight moved by railroad (or boats if there was a water connection). Since the U.S. is so vast, a long train trip meant sleeping overnight on the train. That was miserable and uncomfortable, until George M. Pullman

invented the Pullman Palace Car.

They were luxurious and people gladly paid a premium to ride in one. The cars rode on 16 wheels instead of the standard 8, so the ride was smoother. They had a ventilation system to keep out soot. Pullman also invented a dining car, so that the passengers didn’t have to bring their own food or disembark at a bad train station restaurant. Pullman was a genius at publicity, too, a master at “branding” before that was even a word: somehow he started the rumor that Lincoln’s casket’s final voyage to Springfield was on a Pullman car (it wasn’t).

Pullman had a monopoly and he collected a royalty from every railroad that used his cars, which was every one that carried passengers.

The Town of Pullman

Pullman wasn’t content to just run a monopoly and collect tons of money. No, he wanted his own town for workers to live in! They couldn’t buy the houses; they could only rent them and the rent was deducted from their paychecks (eventually that was outlawed, so they’d get two paychecks: one for the rent, and one for what was left. They’d just sign over the rent check back to the company).

Workers weren’t required to live there. Rents were actually a little higher than in the surrounding villages, especially in the Panic of 1893, but there was a belief among the workers that you’d be favored if you lived there. Plus, it was a short walk to the factory.

They were nice houses and people still live in them today. The company also provided parks, activities, and a church, but no taverns or brothels were allowed. Pullman wanted a wholesome family environment.

An article by Richard Ely in Harper’s Magazine, Feb. 1885, is fascinating. He spent two weeks visiting the town. Here are some excerpts:

one of the most striking peculiarities of this place is the all-pervading air of thrift and providence. The most pleasing impression of general well-being is at once produced. Contrary to what is seen ordinarily in laborers' quarters, not a dilapidated door-step nor a broken window, stuffed perhaps with old clothing, is to be found in the city. The streets of Pullman, always kept in perfect condition, are wide and finely macadamized, and young shade trees on each side now ornament the town, and will in a few years afford refreshing protection from the rays of the summer sun.

It even had a shopping mall, the “Arcade”, although they didn’t call it a mall.

Outside of the home one finds other noteworthy provisions for the comfort, con-venience, and well-being of the residents in Pullman. There is a large Market-house, 100 by 110 feet in size, through which a wide passage extends from east to west. This building contains a basement and two stories, the first divided into six-teen stalls, the second a public hall. The dealers in meat and vegetables are con-centrated in the Market-house. The finest building in Pullman is the Arcade, a structure 256 feet in length, 146 feet in width, and 90 feet in height. It is built of red pressed brick, with stone foundations and light stone trimmings, and a glass roof extends over the entire wide central passage. In the Arcade one finds offices, shops, the bank, theatre, library, etc. As no shops or stores are allowed in the town outside of the Arcade and Markethouse, all shopping in Pullman is done under roof—a great convenience in wet weather, and a saving of time and strength.

I include this part just because those dollar amounts are so charming:

There are over fifteen hundred buildings at Pullman, and the entire cost of the town, including all the manufacturing establishments, is estimated at eight millions of dollars. The rents of the dwellings vary from $4 50 per month for the cheapest flats of two rooms to $100 a month for the largest private house in the place. The rent usually paid varies from $14 to $25 a month, exclusive of the water charge, which is generally not far from eighty cents. A five-roomed cottage, such as is seen in the illustration, rents for $17 a month, and its cost is estimated at $1700, including a charge of $300 for the lot. But it must be understood that the estimated value of $1700 includes profits on brick and carpenter work and everything furnished by the company, for each industry at Pullman stands on its own feet, and keeps its own separate account. The company's brick yards charge the company a profit on the brick the latter buys, and the other establishments do the same ; consequently the estimated cost of the buildings includes profits which flowed after all into the company’s coffers.

You’re wondering, “Man, the rent is so cheap! But what were the workers paid?” Glad you asked:

The wages paid at Pullman are equal to those paid for similar services elsewhere in the vicinity. In a visit of ten days at Pullman no complaint was heard on this score which appeared to be well founded. Unskilled laborers—and they are perhaps one-fourth of the population—receive only $1 30 a day; but there are other corporations about Chicago which pay no more, and Pullman claims to pay only ordinary wages. Many of the mechanics earn &2 50 or $2 75 a day, some $3 and $4, and occasionally even more. Those who receive but $1.30 have a hard struggle to live, after the rent and water tax are paid. On this point there is unanimity of sentiment, and Pullman does comparatively little for them, and the social problem in their case remains unsolved. They are crowded together in the cheap flats, which are put as much out of sight as possible, and present a rather dreary appearance, although vastly better than the poorer class of New York tenements.

When we say “benevolent despotism” remember that second word: despotism.

One gentleman [the author], whose position ought to have exempted him from it, was "warned" in coming to Pullman to be careful in what he said openly about the town. It required recourse to some ingenuity to ascertain the real opinion of the people about their own city. While the writer does not feel at liberty to narrate his own experience, it can do no harm to mention a strange coincidence. While in the city the buttons on his wife's boots kept tearing off in the most remarkable Manner, and it was necessary to try different shoe-makers, and no one could avoid free discussion with a man who came on so harmless an errand as to have the buttons sewed on his wife's boots. This was only one of the devices employed. The men believe they are watched by the " company's spotter," and to let one of them know that information was desired about Pullman for publication was to close his lips to the honest expression of opinion. The women were inclined to be more outspoken.

Eugene Debs and the American Railway Union

Did you say “paternalism?” We’ll go with that. If George Pullman was a father figure, he was a stern and distant father. He was the opposite of Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, credited later at HP with “management by walking around,” because they wanted to meet their workers and hear their concerns in person. Pullman didn’t even have his office in the factory; he and his executives were in the Pullman Building in downtown Chicago, 14 miles away. I doubt that many of the workers even knew what he looked like.

There was no union for all the workers in the factory. There were “craft unions” for workers with specific skills, like firemen, brakemen, and engineers, and those were well established, conservative, and cooperative with management. They never struck.

Pullman was unalterably opposed to a general union, but an up-and-coming, charismatic ex-politician from Terre Haute, Indiana named Eugene V. Debs

wanted to start one, called the American Railway Union. He won a stunning victory in a dispute with the Great Northern Railroad, which agreed to arbitration with the union. This made him a hometown hero in Terre Haute. But then he got sucked in by events at the Pullman factory, and although he tried valiantly to keep it legal, things got well beyond his control.

The Depression of 1893

You’ve heard of The Great Depression. But prior to that, the Panic of 1893 was the worst depression the U.S. had ever seen. Unemployment reached 20%, and back then, there was no unemployment insurance or other forms of social safety net. The New Deal was still 40 years in the future.

Pullman saw a huge drop in orders for his cars. So naturally, he laid off workers, closed his Detroit plant, and cut wages for many of the workers he kept on. Were you thinking that he’d be a good father and also cut their rents to compensate? No, rents stayed the same. He refused to reconsider any of it.

On May 7, a group of workers went to the Pullman Building downtown to discuss their grievances, which included not only the pay and the rents, but abusive treatment by factory foreman. They met with Thomas Wickes, a Vice President of the company, and eventually Mr. Pullman himself. Both explained that wages could not be increased, nor could rents be reduced. The matter of arbitration was expressly ruled out. The company continued to pay its dividends to shareholders, though.

They cleverly deflected the conversation to the alleged bad treatment by foremen, expressing concern and vowing to stop it. Pullman gave his word that organizers would not face retaliation for having met with him. As far as Wickes and Pullman were concerned, it was a triumph. They’d listened, they’d explained the numbers, case closed.

The next day, three of the organizers were nonetheless laid off or told that there was no work for them. An all-night meeting was held by the workers, and “strike” was on everyone’s mind. George Howard, an organizer for the union, urged caution. But by now the workers were in no mood for moderation. On May 12, they walked off the job and the factory was closed.

The Fuse is Lit

The Pullman workers went out on strike. At first, it seemed like a picnic. The mayor of Chicago backed them. Contributions to their relief fund flowed in. The Pullman management ignored them, calling them ex-employees with no more rights than the random man on the street. The company still had rental revenue coming in from their railroad contracts, but no one was buying any new cars. If some railroad did want one, Pullman had plenty in inventory.

The union got increasingly desperate. The workers had no income and clearly shutting down the factory wasn’t hurting Pullman much. So they decided to ask union members around the country to refuse to run any trains that contained a Pullman car. This would shut off the rental money.

A local dispute now affected the whole country. Suddenly the widespread hatred of the railroads had a focus.

The Chicago Tribune, a staunchly pro-business paper, supported the company wholeheartedly. On June 26, this is the editorial they ran (“editorials” and the news were mixed together then, so there wasn’t really a separate editorial page like there is now).

SLEEPING CARS TO BE TIED UP—RIGHTS OF THE PEOPLE NOT CONSIDERED. After several days of deliberation the new railroad organization called the American Railway Union has decided to ask the railroad employes of the country to refuse to handle Pullman sleeping cars, or to allow them to be attached to passenger trains. The object is to bring additional pressure to bear on the Pullman company to force it to pay higher wages to employes who quit work and surrendered their situations a couple of months ago because they did not think they were getting enough pay, they demanding the same number of dollars as received last year when money had less purchasing power. Week before last, when some of the old employes at Pullman appeared before the ARU convention and described their unhappy situation, many delegates got excited and clamored for an immediate boycott. But no one got excited over the prospect of forcing people who for thirty years have been accustomed to use sleeping cars suddenly to do without them. No one in that convention suggested timidly that hundreds of thousands of people would be inconvenienced seriously—not to use a stronger phrase—by the sudden stoppage of sleeping cars throughout the West or Union. The whole traveling public, and not merely those who use sleepers, will have the screws put on them, though they are in no way parties to the dispute. The head of the Railway Union announces that if injunctions are served on them by any railroad we will immediately tie up the entire railway system. I should not be surprised if this boycott would bring about a general railroad strike. If it does we shall come out of it with every railway employe in the country in our ranks and with every grievance adjusted. This is a good time to do it. So if the railway companies refuse to break contracts they have made for the hauling of sleeping ears, or if courts attempt to intervene to protect the public, travel throughout the Union must cease for this season of the year. The serenity with which the head of a railway labor organization contemplates the possible distress and unhappiness of millions of the American people is cynical and revolting. This utter indifference to the rights and comfort of the public or of innocent third parties who have nothing to do, directly or indirectly, with one of these conflicts between capital and labor on a dispute about wages shows a lack of humanity on the part of the proposed boycotters. one would imagine that the American Railway Union, at the same time that it was determining to injure the innocent traveling public, would apologize to those who use sleeping cars and express profound regret that the steps to be taken against the company would seriously interfere with their comfort and health. But there has been nothing said as yet to show that the union cares a fig whether the masses of the people are incommoded and harmed or not, provided Pullman can be hurt. Perhaps it is natural that men who are out on a strike should forget the rights of third parties. They are in the heat of a personal contest, a sort of civil war, and they think of nothing else. But while these Pullman strikers joined the American Railway Union at the time they struck the other members of that organization cannot have such an overwhelming interest in that controversy as to be forgetful utterly of the fact that a stoppage of the running of several thousand sleepers in the United States is a direct attack on multitudes of innocent individuals. Are the unquestioned rights of the many to be assailed to protect the alleged rights of a few? Where does the American Railway Union find a legal or equitable argument fur that? Is there no other way of settling the dispute about wages these hard times?

“Is there no other way of settling the dispute about wages” — yes, it’s called '“bargaining,” and then “mediation,” and if that fails, “arbitration.” But Pullman insisted that there was “nothing to arbitrate.”

Strikes do affect the general public; there’s no question about that. But unions have a well-established right to strike nowadays.

But Then What?

So now the call for help had gone out. Would railroad workers answer it? An Illinois Central train pulled out of the station with Pullman cars attached, and the answer appeared to be No. But let’s let the Tribune tell the tale:

SEVERAL TRAINS STOPPED

Fears Expressed That All Traffic Will Be Paralyzed Today

PULLMAN BOYCOTT HANGING FIRE

The Illinois Central railway from Chicago to Homewood is in the hands of its enemy the American Railway Union. If the expectations of the leaders of the labor organization are realized the service of the road will be paralyzed today and not a train, either through, suburban, or freight, will leave or enter the city. Last night the boycott against Pullman cars turned into a strike against the railroad company, the switchmen going out at 8 o’clock. They were followed by the switch tenders, and at midnight were joined by the switch tower operators. This was a surprise to the officials of the road, but it was a well-planned move on the part of Debs, Howard. and the other leaders of the anti-Pullman war. They secretly organized these men and resolved to make a test of their strength against the road on which they are strongest and best organized.

It is said that at 7 o'clock this morning the switchmen and switch tenders of all lines centering in the Union depot will go out. This will affect the Ft. Wayne, Pan Handle, Burlington. Milwaukee and St. Paul, and the Alton. In the event of such a strike a serious blockade attempt was made to get an Illinois Central suburban train through, but a man in the crowd threw himself down on the rails in front of the engine and the engineer refused to move the train.

There were only ten policemen on duty in Grand Crossing when the mob gathered, and Chief Brennan was telephoned to for help. He responded by instructing Inspector Hunt of the Hyde Park Station to proceed with ten men to the scene of the trouble, which was done. Officer Dorrigan. who was in charge of a detail of nine men at the Twelfth street depot, and ten Illinois Central detectives were also hurried to Grand Crossing.

The latter detachment went out on the Diamond special, which left at 9:20, twenty minutes later than its schedule time. This train, which carried a number of delegates and politicians bound for the Democratic State convention at Springfield, was stopped along with the others. Two Pullman coaches were attached to it. In addition to the police Assistant General Superintendent Hartigan and several other Illinois Central officials were on the Diamond special. Mr. Hartigan went into the tower, opened the gates, and traffic was resumed.

Policemen Gather

Meanwhile the force of police was being rapidly increased by detachments from neighboring stations, and by 10 o’clock was strong enough to keep the mob back. Frank G. Hackett, the gate tender at Grand Crossing, was persuaded by Pullman strikers and members of the American Railway Union to leave his position. There was no one else who had authority to open and shut the gates. Hackett left his post at 7 o'clock, just as a suburban train from the north approached the crossing and whistled for the gates to open. There was no response from the gateman and the train was compelled to stand there. Then every few minutes another train came to a standstill. The switchmen also refused to turn the switches to allow the embargoed trains to pass.

Inspector Hunt was seen at the crossing. He said he had seventy-five men on the scene and 200 in reserve and was prepared to suppress any disturbance that might arise. A switchman on the ground said that all of his craft from Burnside to Lake street had struck—125 men in all. Engineers and other employés said they had no connection with the strike, that it was confined solely to switchmen.

Asks for Police Protection

When General Manager Charles Watts of the Northwestern Division of the Pennsylvania heard of the trouble he hurried to Chief Brennan's office, where he asked for protection for the company’s property. |

*As I understand it, said Mr. Watts, "an irresponsible mob gathered around our gatemen who throw the signals at the intersection of the Illinois Central and Fort Wayne tracks and either forced or coaxed them to quit work. Of course this left the crossings unprotected and trains could not pass. The men who caused this are not members of the American Railway Union unless they were Pullman strikers. Few of our men are connected with the organization. Train No.9, a fast express containing a United States mail car, due at the Union Depot at 9 p. m., was held up twenty-five minutes. Train No. 66, a freight, bound east, was held up for two hours. Finally our station agents threw the signals. This released the trains at once.

Government May Take a Hand

‘If the responsibility for this trouble at Grand Crossing can be located the government is likely to take a hand in the fight. The stopping of the mail train is a serious offense, and an investigation will be demanded. I am confident, however, that the Pennsylvania system will suffer very little by the boycott. We have many Pullman cars and are determined to operate them, American Railway Union or no American Railway Union. I have been all over my division and know how the men feel. They are not in sympathy with the movement. We are so confident of the outcome that the Pennsylvania road bas not considered special defensive measures. We believe the regularly delegated authorities are equal to the emergency. There may be hitches for a few days, but that will be all. We have not had a particle of trouble in our yards and have every assurance that our switchmen will be loyal.”

During the time of the blockade Michigan Central trains passed several times, the gates being swung by some one of the strikers. As the Wagner cars passed by they were greeted by the crowd with shouts of: “Those are the cars to run. They're all right,” and similar expressions. The passengers in the Pullman cars were advised by the crowd that they might as well decide to travel in a common coach, as no more Pullman cars would be allowed to pass Grand Crossing.

At Kensington and Burnside no trouble occurred, though groups of Pullman strikers and American Railway Union men assembled at each place.

It’s really amazing how much text they included in a newspaper back then. I’m not going to OCR all this! There are seven columns on that page, this being only part of three.

People had a lot of time to read back then, I guess. No radio, no TV, obviously no smartphones.

That’s It For Now

We’ll continue the story next week. Stay tuned.

(Note the part about mail trains. This became a key issue for the government, even though Debs and the union would have been more than happy to run trains with only mail cars and freight cars. The railroads insisted on including Pullman cars.)

Appendix

Photo Journalism

It’s really amazing to me how few photographs there are of the principals in this drama, and especially how there are no "on the scene” photos. Nowadays, a news outlet would send out a camera crew along with their reporter. Back then, it hadn’t quite started yet. I think the exposure times for film were just too long, and cameras too big & expensive.

I did find this actual photo of the aftermath of one of the freight car burnings:

Chicago History Museum, ICHi-061430

Very interesting. This was mentioned in the book "Low Life" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City_draft_riots

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Sante They said it was the closest NYC ever got to anarchy.